Ecological Ethics in the Age of Climate Crisis

A Question Raised by the Climate Crisis

Global temperatures have already risen close to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Heatwaves, floods, wildfires, and droughts are no longer rare disasters but recurring realities. Climate change is no longer a future threat—it directly affects human survival today.

This reality forces a fundamental ethical question:

Should human rights and interests always come first, or does nature itself deserve moral and legal priority?

1. Anthropocentrism: Humans as the Sole Bearers of Rights

1.1 Philosophical Foundations of Human-Centered Thinking

Modern Western thought has long placed humans at the center of moral consideration. Since Descartes’ declaration “I think, therefore I am,” nature has largely been treated as a resource to be controlled and utilized. Legal and political systems evolved primarily to protect human rights, often excluding non-human entities from moral concern.

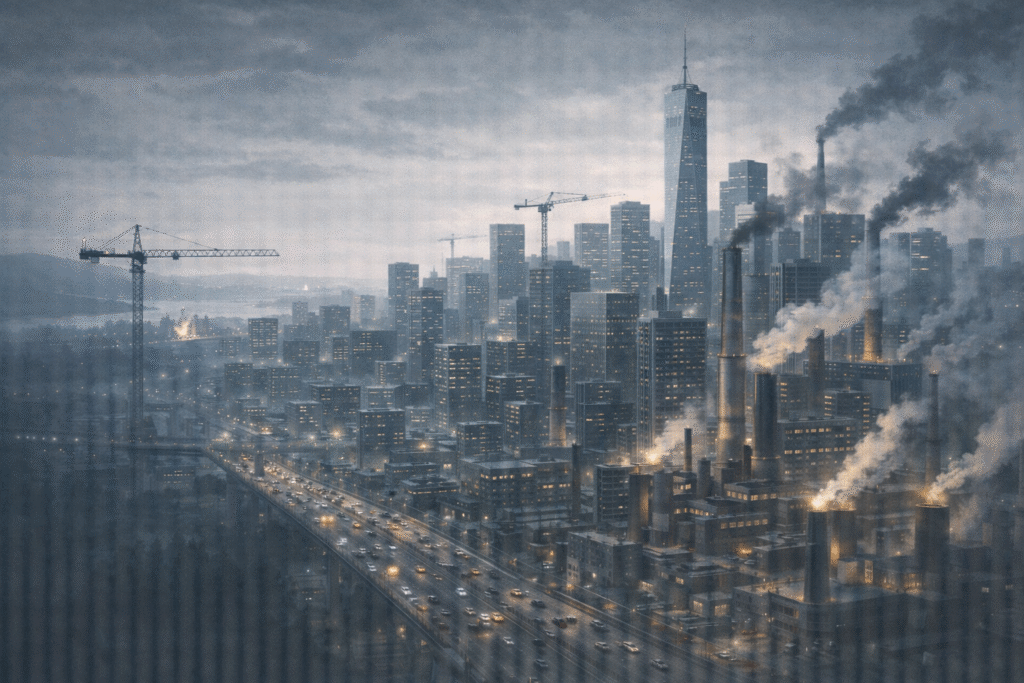

1.2 Development Justified in the Name of Human Benefit

Large-scale development projects—such as dams, highways, or industrial complexes—have historically been justified by promises of economic growth and employment, even when they destroyed ecosystems or displaced communities. These decisions reflect anthropocentrism, the belief that human interests inherently outweigh those of the natural world.

2. The Challenge of Ecological Ethics: Nature as a Moral Subject

2.1 Aldo Leopold and the Land Ethic

In the mid-20th century, this worldview began to be challenged. Aldo Leopold’s concept of the Land Ethic argued that humans are not conquerors of nature but members of a broader ecological community. Soil, water, plants, and animals should be included within the sphere of moral responsibility.

2.2 Legal Recognition of Nature’s Rights

This ethical shift has increasingly entered legal frameworks. Ecuador’s constitution recognizes the rights of nature, and New Zealand granted legal personhood to the Whanganui River, reflecting Indigenous perspectives that view humans and nature as inseparable.

These cases represent a radical departure from seeing nature as property, redefining it instead as a rights-bearing entity.

3. Conflicting Values in the Climate Crisis

3.1 Rights Versus Rights

Climate conflicts often involve competing claims. A forest may serve as a vital carbon sink and habitat, yet local communities may depend on land development for housing and employment. Prioritizing nature may restrict economic rights, while prioritizing development may accelerate ecological collapse.

3.2 Climate Change as a Political and Ethical Crisis

This tension reveals that climate change is not merely an environmental issue but a conflict between rights—human rights versus ecological integrity. The challenge lies in resolving this conflict without sacrificing long-term survival for short-term gain.

4. Bridging Human and Natural Rights

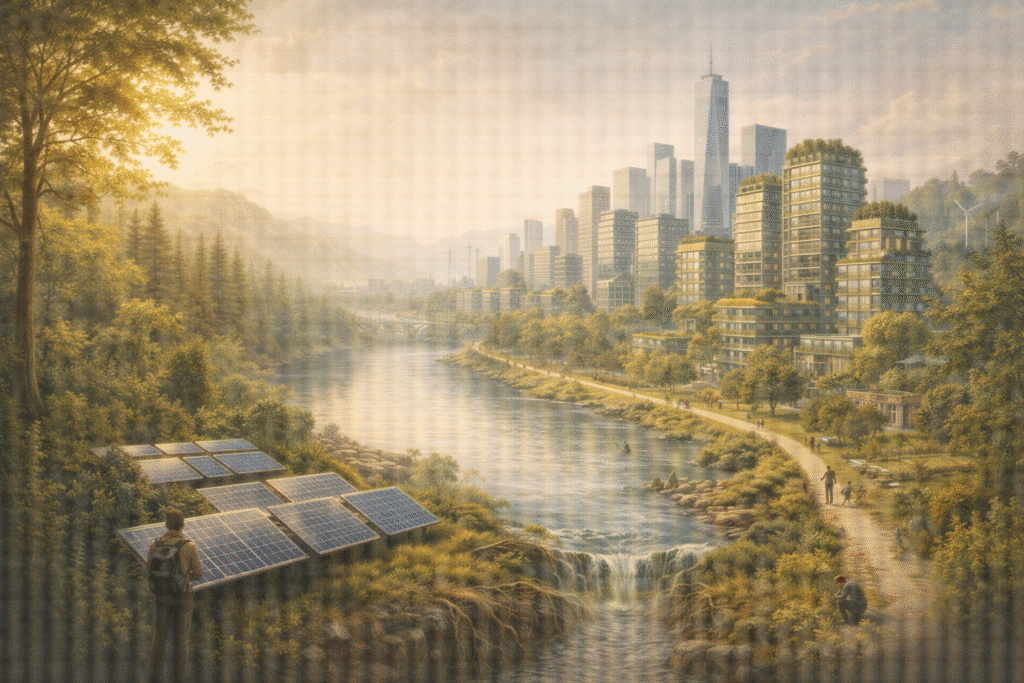

Several approaches seek to move beyond simple opposition:

- Interdependent Rights: Human rights depend on healthy ecosystems—clean air and water are prerequisites for life.

- Intergenerational Justice: Future generations’ rights demand limits on present exploitation.

- Community-Based Perspectives: Indigenous worldviews often treat humans and nature as members of a single moral community.

5. Ecological Ethics as a New Social Contract

5.1 Beyond Environmental Protection

Ecological ethics calls for more than conservation policies. It challenges political, legal, and economic systems to redefine responsibility in an age of planetary limits.

5.2 Legal and Moral Innovation

Recent climate lawsuits argue that government inaction violates citizens’ fundamental rights. At the same time, recognizing nature as a rights-holder suggests a future where humans and ecosystems share legal standing.

Conclusion: From Hierarchy to Coexistence

Can nature have rights above humans? Framed as a simple hierarchy, the question leads to endless conflict. Yet the climate crisis reveals a deeper truth: when nature’s rights are violated, human rights ultimately collapse as well.

True solutions lie not in choosing between humans and nature, but in recognizing their interdependence. In an age of ecological limits, justice may no longer belong to humans alone.

References

- Stone, C. D. (1972). Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects. Southern California Law Review, 45(2), 450–501.

→ A foundational legal argument proposing that natural entities should be recognized as legal subjects rather than mere property. - Naess, A. (1989). Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy. Cambridge University Press.

→ Establishes the philosophical foundations of deep ecology, rejecting anthropocentrism in favor of intrinsic ecological value. - Leopold, A. (1949). A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press.

→ A classic text in environmental ethics introducing the Land Ethic and redefining humans as members of a biotic community. - Singer, P. (1993). Practical Ethics. Cambridge University Press.

→ Expands ethical consideration beyond humans, including animals and environmental concerns. - Jonas, H. (1984). The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age. University of Chicago Press.

→ Argues for ethical responsibility toward future generations and the natural world in an era of technological power.

Leave a Reply