— The Psychology of Sweetness and Behavioral Conditioning

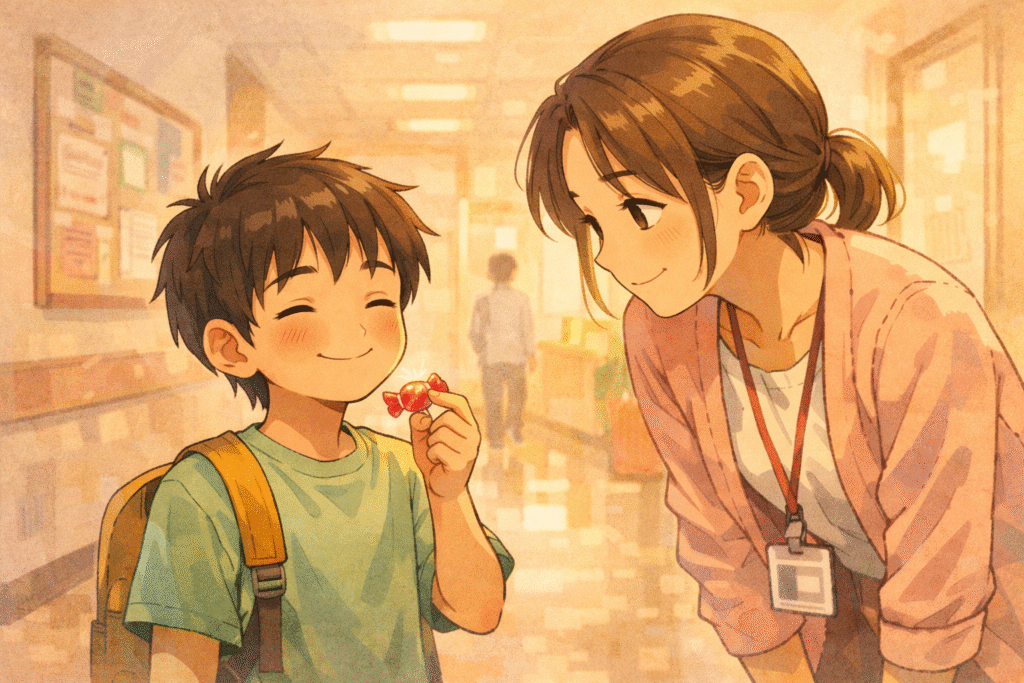

“Be brave and you’ll get candy.”

“Finish your homework and here’s a treat.”

“Don’t cry at the doctor, and you can have one.”

Across many cultures, candy has become the universal symbol of reward for children.

But why candy?

Why not toys, books, or something else?

Why has a small, sweet object become the emotional shorthand for praise?

1. Sweetness Is Biologically Rewarding

Humans are wired to prefer sweetness from birth.

Breast milk itself is sweet, and infants quickly show a strong positive reaction to sugary tastes.

From an evolutionary perspective, sweetness signals energy-rich carbohydrates — a valuable resource in harsh environments.

In other words, sweetness equals survival.

Candy, therefore, triggers immediate pleasure responses in the brain’s reward system.

For children, whose emotional regulation is still developing, such immediate reinforcement is especially powerful.

2. From Luxury to Behavioral Tool

Sugar was once rare and expensive.

But after industrialization made sugar widely available in the 19th century, candy transformed from a luxury item into a mass-produced consumer good.

At the same time, modern childhood emerged as a protected and emotionally significant stage of life.

Candy began to function not merely as food, but as a behavioral incentive.

“Good behavior = sweet reward.”

This simple formula reinforced compliance, courage, and discipline.

Over time, candy became embedded in parenting, schooling, and even medical routines.

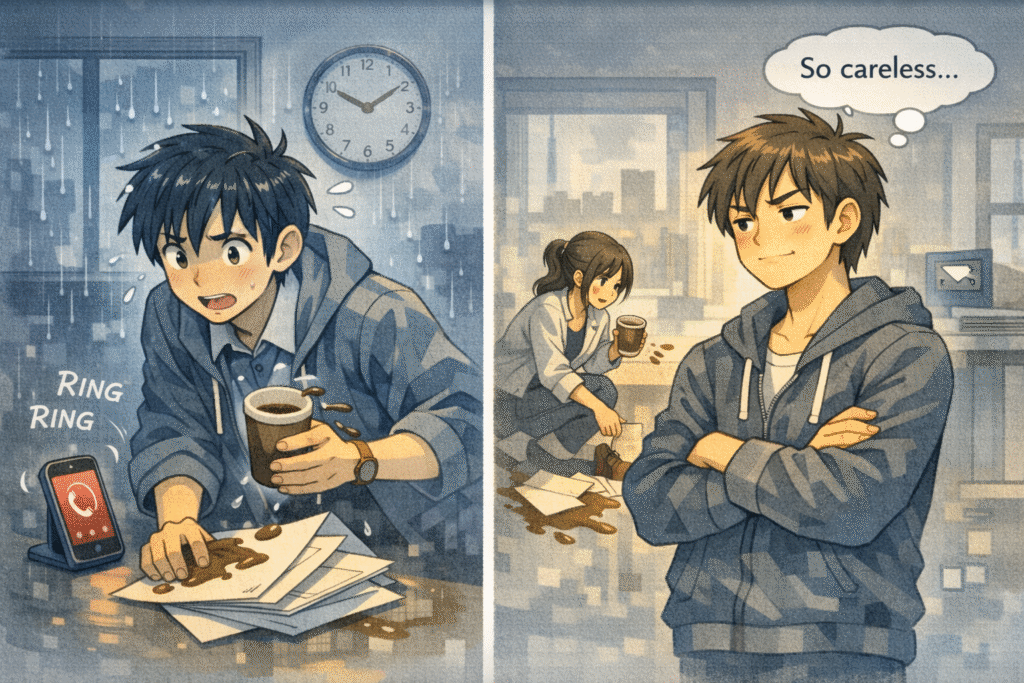

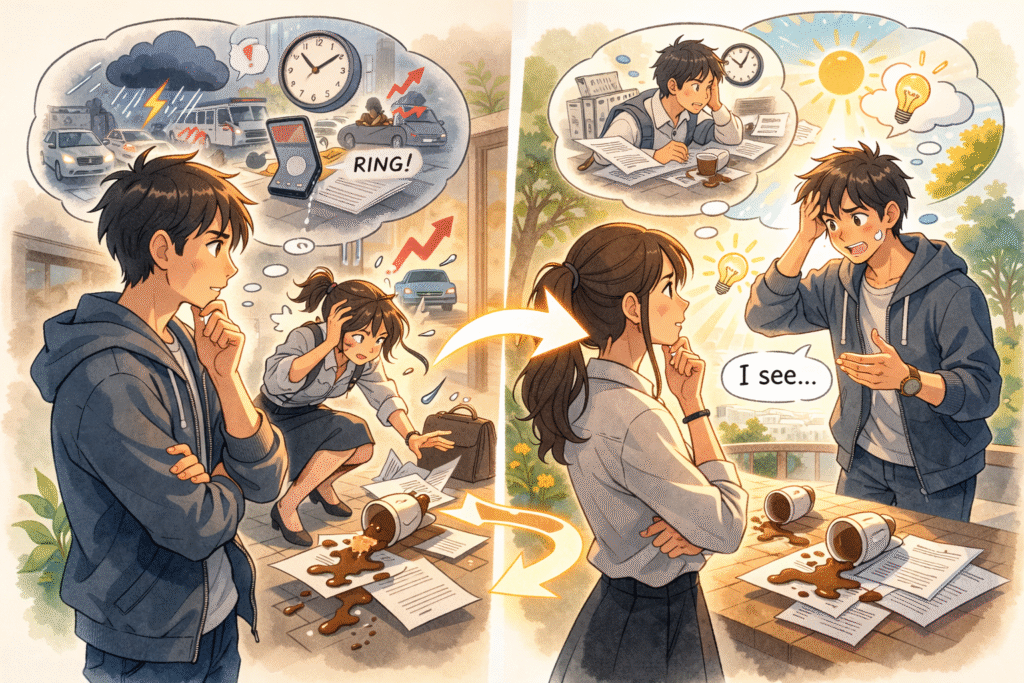

3. Candy as Emotional Recognition

When adults give candy, they are not only giving sugar.

They are giving acknowledgment.

“You did well.”

“I see your effort.”

“You were brave.”

Candy becomes a tangible symbol of recognition.

For a child, this small object carries emotional meaning far beyond its size.

It marks a moment of approval and belonging.

4. Cultural Ritual and Symbolic Memory

Today, candy is deeply woven into childhood rituals:

Halloween trick-or-treating

Birthday parties

Doctor’s office reward baskets

Holiday celebrations

Through repetition, candy has become ritualized.

It is no longer simply sweet.

It is symbolic.

It represents courage, obedience, growth, and celebration.

These associations become part of early emotional memory.

Conclusion: A Small Object, A Big Meaning

Candy is not merely sugar.

It is a compact emotional language.

It links biology (reward circuits),

economics (mass production of sugar),

and culture (ritualized childhood practices).

For children, candy often means:

“You did well.”

“You are loved.”

“You belong.”

Perhaps that is why its sweetness lingers far beyond taste.

Related Reading

The subtle emotional layering behind childhood memories and symbolic objects is further explored in The Texture of Time — How the Mind Shapes the Weight of Our Moments, where lived experience gradually transforms simple sensations into lasting meaning.

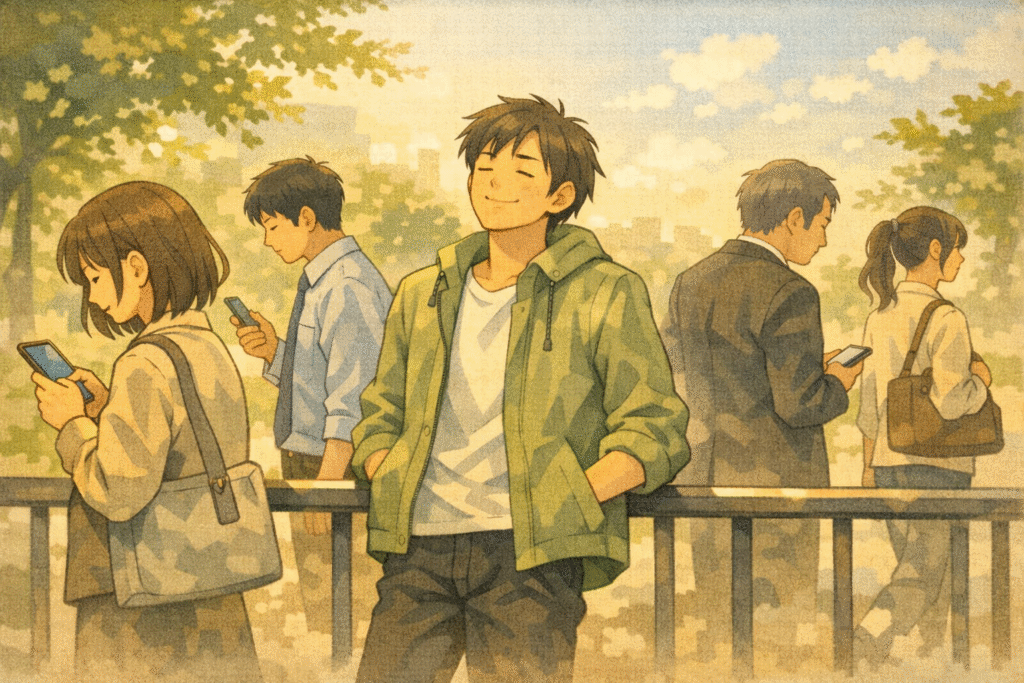

In the digital age, the way small pleasures evolve into social comparison is examined in How Social Media Amplifies Feelings of Lack and Comparison, where personal satisfaction can quietly shift into a metric of visibility and validation.

References

1. Mintz, S. W. (1985). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Viking Penguin.

→ Mintz explores how sugar became embedded in systems of power, consumption, and social meaning, showing how sweetness evolved from luxury to everyday reward.

2. Allison, A. (2006). Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. University of California Press.

→ Allison examines how children’s consumer culture connects toys, treats, and reward structures, highlighting how material goods mediate emotion and identity.

3. Zelizer, V. A. (1994). Pricing the Priceless Child. Princeton University Press.

→ Zelizer analyzes the changing cultural value of children in modern society, explaining how material tokens such as gifts and treats became expressions of emotional recognition.