Introduction — Those Left Behind in a Connected World

We now live in a world where AI assistants manage our schedules, banking happens on smartphones, and education unfolds on digital platforms.

But not everyone can access these tools—or understand how to use them.

What feels like a simple click for some becomes an insurmountable barrier for others.

This is where the term “digital refugee” emerges.

Technology was meant to connect us, but for those excluded from the digital ecosystem, it creates a new form of social isolation and inequality.

Today, the vulnerable population is no longer defined only as

“those without internet,”

but increasingly as

“those who cannot interact with AI.”

1. What Are Digital Refugees? — Invisible Migrants of the Information Age

Digital refugees are not people crossing physical borders.

They are people pushed to the margins of society because they cannot cross the technological border of the digital world.

This includes individuals who lack:

- access to devices

- stable internet

- digital literacy

- the ability to use AI-driven systems

For example:

When government services move entirely online, many seniors or low-income citizens struggle with complex application systems. As a result, they become excluded—not legally, but digitally.

UNESCO defines this as a Digital Access Rights issue, arguing that access to the internet and digital tools is now a fundamental human right.

This is no longer a matter of convenience but a matter of dignity and civic participation.

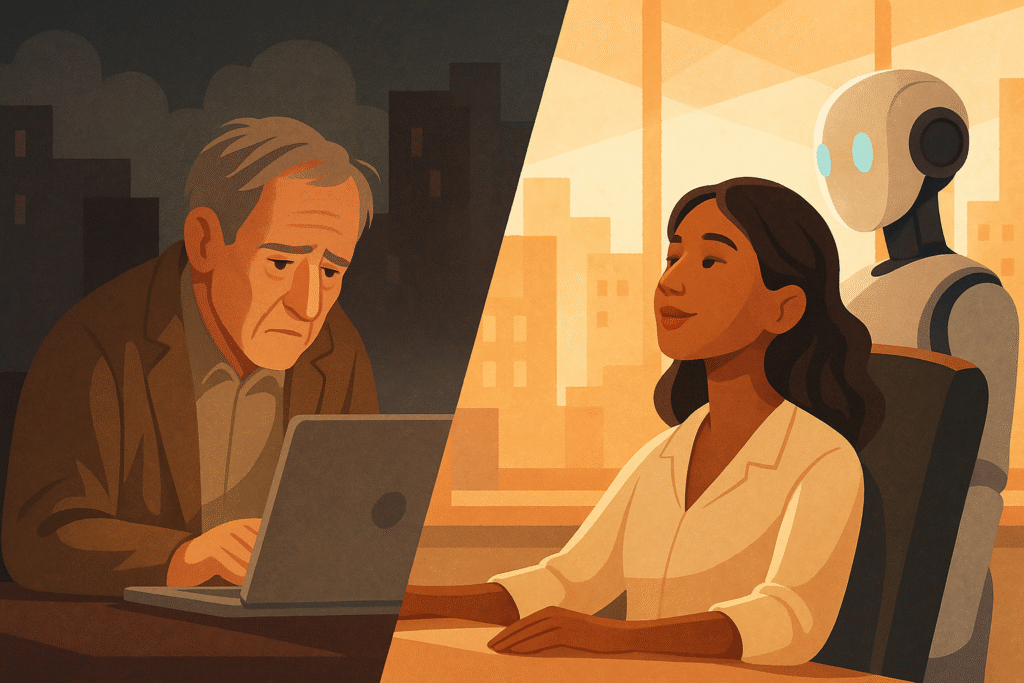

2. Technology’s New Inequality — Who Truly Has the Freedom to Connect?

AI and automation bring efficiency, but they also sort society into new classes:

- those who understand and utilize digital tools, and

- those who cannot

People with advanced digital skills gain better jobs, information, and influence.

Those without them gradually lose access to healthcare, finance, transportation, and even public voice.

For someone unfamiliar with smartphones, tasks like medical appointments, transportation schedules, banking, and government forms become overwhelming.

In such cases, technology stops being a tool and becomes a barrier.

AI also filters the information we see.

Low digital literacy increases exposure to narrow or biased content, reinforcing social division and weakening democratic participation.

Thus, digital inequality is not just economic—it is structural, cultural, and political.

3. Expanding Human Rights — Technology Access Is Not a Luxury but a Right

In 2016, the UN Human Rights Council declared internet access a prerequisite for freedom of expression.

Since then, Digital Access Rights have become central to global human rights discourse.

This shift demands that states treat digital inclusion as a form of social welfare.

Some examples:

- Finland declared broadband access a legal right in 2010.

- South Korea is expanding digital education for seniors and people with disabilities.

Yet despite progress, rural communities, low-income citizens, and elderly populations remain cut off from AI-driven services.

As AI becomes embedded in public policy, education, and healthcare,

digital literacy becomes a condition for survival, not a privilege.

People who cannot interact with AI systems risk becoming citizens who exist but cannot participate.

4. Is Technology a Liberation—or a New Language of Discrimination?

AI reads text, interprets images, and even writes.

But behind this intelligence lies:

- biased data

- unequal representation

- structural discrimination

AI often replicates the inequalities it learns.

For instance, if AI hiring systems are trained on biased historical data, they reproduce those disparities—reinforcing societal injustice under the illusion of neutrality.

Thus, digital inequality expands beyond “access” to become a question of design:

Who is technology built for?

Whose needs were ignored?

Who gets left out of the system entirely?

AI-era human rights must address not only access but also inclusive design.

5. Conclusion — Does Technology Make Us More Equal?

Technology can enhance human life—but only if its benefits are shared.

Digital refugees are not people who “failed to adapt.”

They are people whom the system failed to include.

In the AI era, equality requires more than distributing devices.

It requires rethinking how technologies are built, implemented, and accessed.

Digital literacy is the new civic education.

Digital access is the new condition of existence.

We must ask:

“Does technology liberate humanity—or does it divide us further?”

The answer depends not on the machines,

but on the choices we make as a society.

📚 References

1. Gurumurthy, A., & Chami, N. (2020). Digital Justice: Reflections on the Digitalization of Governance and the Rights of Citizens. IT for Change.

https://itforchange.net

A foundational work examining how digital governance reshapes citizenship, rights, and power structures.

2. UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. UNESCO Publishing.

https://unesco.org

A global report proposing a future-oriented educational framework with emphasis on equity, digital access, and social justice.

3. Selwyn, N. (2016). Education and Technology: Key Issues and Debates. Bloomsbury Publishing.

https://bloomsbury.com

A critical analysis of technology’s promises and limits in education, challenging techno-optimism and highlighting structural inequalities.

4. Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019). The Costs of Connection: How Data is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Stanford University Press.

https://sup.org

An influential critique of the data economy arguing that digital systems extract, commodify, and govern human experience.

5. Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin’s Press.

https://us.macmillan.com

A groundbreaking investigation into how automated decision systems disproportionately harm marginalized communities.

Leave a Reply