How Absence Shapes Power in Advertising and Design

1. White Space as Silent Communication

1.1. Visual Silence That Commands Attention

When we look at advertisements or posters, our eyes are usually drawn to bold images and striking slogans.

Yet many designers argue the opposite: empty space, or white space, often carries the strongest message.

White space functions like silence in conversation.

It appears to say nothing, yet that very absence forces the viewer to pause, slow down, and focus.

1.2. Less Information, Stronger Impact

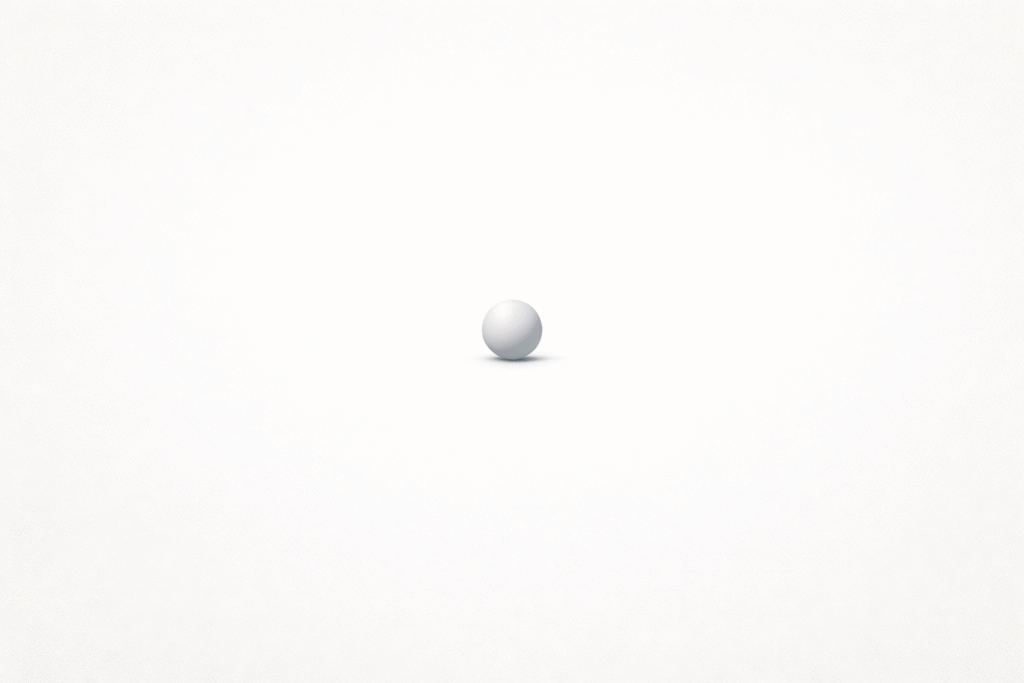

Apple’s advertising offers a clear example.

A single product is placed at the center, surrounded by vast empty space.

Nothing distracts the viewer—attention naturally converges on the object itself.

In poster design, the same principle applies.

By intentionally removing excess elements, the remaining message becomes sharper and more memorable.

White space, then, is not “nothing”; it is a strategic choice for emphasis.

2. Cultural Meanings of White Space

2.1. East Asian Aesthetics: Emptiness as Possibility

Perceptions of white space differ across cultures.

In East Asian aesthetics, empty space has long been treated as an essential artistic element.

In ink painting, wide blank areas do not represent absence or lack.

They invite imagination, symbolize nature, and allow meaning to emerge indirectly.

Here, emptiness is not deficiency—it is potential.

2.2. Western Design and the Rediscovery of Minimalism

Western commercial design historically favored filling space with information.

More text, more images, more explanation were believed to increase persuasion.

Today, however, global visual culture has shifted.

Minimalist layouts and generous white space now signal refinement, confidence, and sophistication.

White space has become a shared visual language across cultures.

3. White Space as a Language of Power

3.1. The Authority of Not Explaining

The ability to use white space often reflects privilege.

Leaving large areas empty—especially in expensive advertising spaces—signals the freedom to waste resources.

White space suggests a position where explanation is unnecessary.

It communicates confidence: this needs no justification.

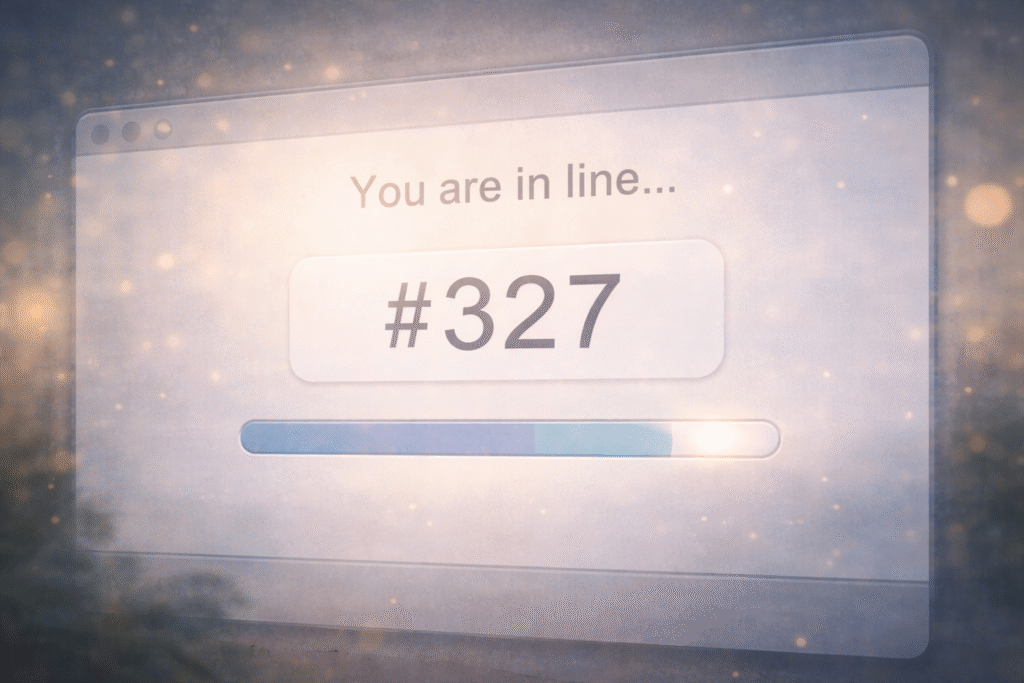

3.2. Luxury Branding and Symbolic Distance

Luxury brands frequently display a single product against a blank background.

The message is subtle but powerful:

“We do not need to persuade you—our value is self-evident.”

In this sense, white space operates not only as a design technique but as a symbol of status and authority.

4. White Space in the Digital Age

4.1. Information Overload

Smartphone screens, social media feeds, and digital ads bombard users with endless content.

The result is cognitive fatigue and fragmented attention.

4.2. White Space as Psychological Relief

In this environment, white space becomes a form of relief.

Google’s minimal homepage or clean interface designs demonstrate how emptiness can restore calm.

Amid digital excess, white space signals clarity, trust, and stability.

It functions as a psychological pause, not merely a visual one.

5. From Design to Everyday Life

5.1. White Space Beyond Graphics

The logic of white space extends beyond design:

- White space in conversation: allowing silence instead of constant speech

- White space in time: leaving unscheduled moments in daily life

- White space in relationships: accepting distance without anxiety

5.2. The Question of What to Remove

White space ultimately asks a deeper question—not about what to add, but what to remove.

It challenges the assumption that fullness equals value.

Conclusion

White space is not absence—it is a deliberate strategy and a form of power.

In advertising and graphic design, it sharpens messages, signals authority, and reflects cultural values.

In an age of digital overload, white space becomes more than a visual choice.

It offers psychological balance and social meaning.

The politics of white space ultimately asks us one simple question:

What must we remove for what truly matters to become visible?

References

- Lupton, E. (2014). Graphic Design Thinking: Beyond Brainstorming.

Explores how reduction, simplicity, and empty space function as tools for visual thinking and strategic communication in design. - Heller, S., & Vienne, V. (2012). 100 Ideas That Changed Graphic Design.

Traces major turning points in graphic design history, including the rise of white space as a powerful visual principle. - Hollis, R. (2001). Graphic Design: A Concise History.

Provides historical context for minimalism and the evolving role of empty space in modern visual culture.