Is Technology a Tool—or a New Master?

We live inside technology.

A day without checking a smartphone feels almost unimaginable.

Artificial intelligence answers our questions.

Big data and algorithms shape what we buy, what we read, and even how we form relationships.

On the surface, technology appears to be nothing more than a collection of tools created by humans.

Yet in practice, our lives are increasingly structured by those very tools.

This leads to a fundamental question:

Do we control technology, or has technology begun to control us?

1. The Instrumental View: Humans as Masters of Technology

1.1 Technology as a Human Creation

From this perspective, technology is a product of human necessity and ingenuity.

From fire and basic tools to the steam engine and electricity, technology has always emerged to serve human needs.

Light bulbs illuminate darkness.

The internet accelerates the spread of knowledge.

Smartphones simplify communication.

Seen this way, technology is neutral.

Its impact depends entirely on how humans design, use, and regulate it.

1.2 Human Choice and Responsibility

According to this view, technology does not determine social outcomes.

Humans do.

Whether technology liberates or harms society ultimately reflects political decisions, cultural values, and ethical priorities.

2. Technological Determinism: When Technology Shapes Humanity

2.1 Technology as a Social Force

A contrasting perspective argues that technology is never merely a tool.

This view—often called technological determinism—holds that technology actively reshapes social structures, institutions, and even patterns of thought.

The invention of the printing press did more than increase book production.

It transformed knowledge distribution, fueled religious reform, and reshaped political power.

Similarly, the internet and social media have altered how public opinion forms and how social movements emerge.

2.2 Algorithmic Mediation of Reality

Today, algorithms decide which news we see, which posts gain visibility, and which voices are amplified or silenced.

In such conditions, humans are no longer fully autonomous choosers.

We operate within frameworks constructed by technological systems.

Technology does not simply assist decision-making—it structures perception itself.

3. The Boundary Between Control and Dependence

3.1 Erosion of Human Control

As technology grows more complex, human control often weakens.

- Smartphone dependency: We use devices freely, yet our attention and time are increasingly governed by them.

- Algorithmic curation: We believe we choose information, but often select only from what platforms present.

- AI-driven decisions: In finance, medicine, and hiring, AI systems now generate outcomes that humans merely review.

What appears as convenience gradually becomes a form of governance.

3.2 Technology as a New Power

Technology approaches us with the promise of efficiency and comfort.

Yet beneath that promise lies a quiet restructuring of habits, priorities, and values.

In this sense, technology functions as a new kind of power—subtle, pervasive, and difficult to resist.

4. Freedom, Responsibility, and Ethical Control

4.1 Are We Becoming Subordinate to Technology?

This does not mean humans are powerless.

Technology does not emerge independently of human intention.

Its goals, constraints, and accountability mechanisms are still socially constructed.

4.2 The Demand for Transparency and Accountability

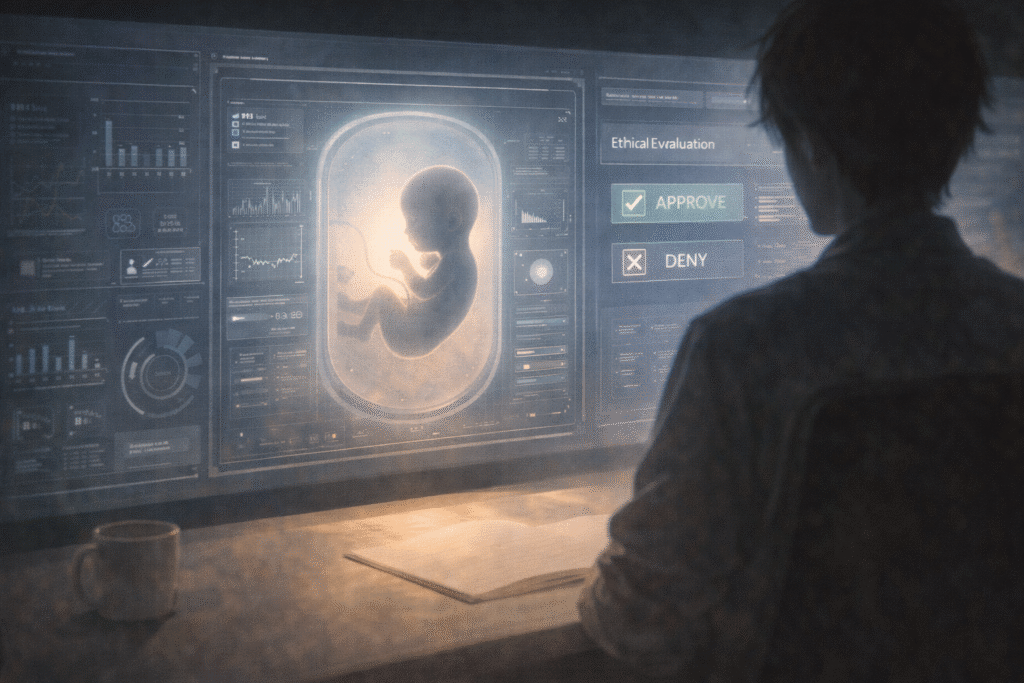

What matters is whether societies demand:

- transparency in how algorithms function,

- clarity about the data AI systems learn from,

- accountability for harms caused by automated decisions.

Without such safeguards, technology risks becoming a system of domination rather than liberation.

Conclusion: Master, Subject, or Both?

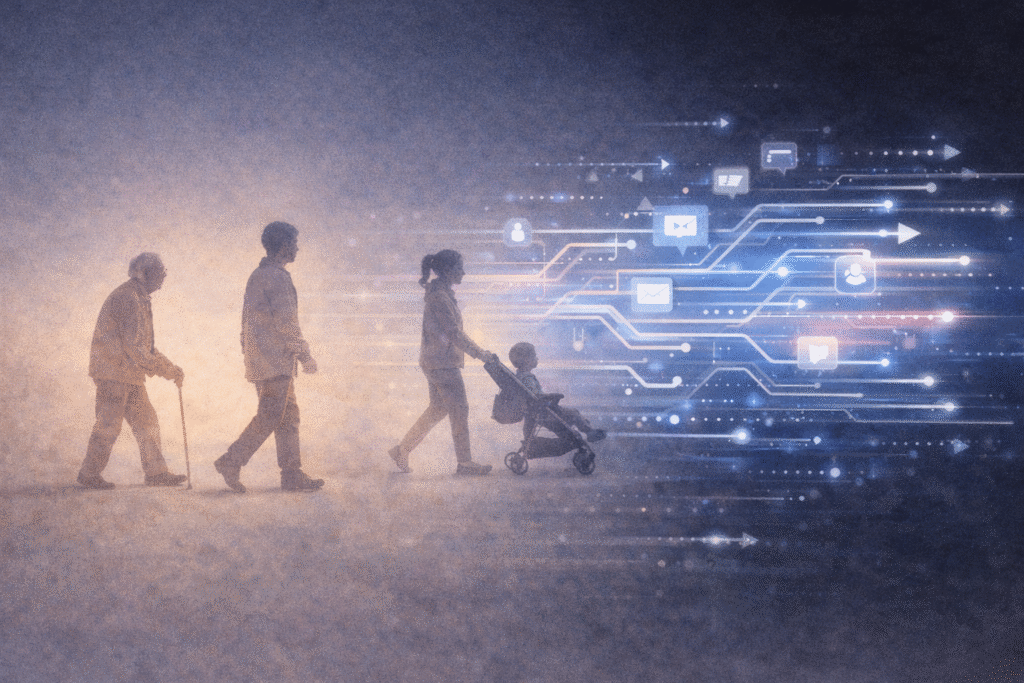

The relationship between humans and technology cannot be reduced to a simple question of control.

Technology is a human creation—but once deployed, it reorganizes society and reshapes human behavior.

In this sense, humans are both masters and subjects of technology.

The decisive issue is not technology itself, but the ethical, political, and social frameworks that surround it.

As one paradoxical insight suggests:

We believe we use technology—but technology also uses us.

Recognizing this tension is the first step toward restoring balance between human agency and technological power.

Related Reading

The tension between technological agency and human autonomy is further examined in Automation of Politics: Can Democracy Survive AI Governance? where algorithmic power and collective decision-making are debated.

At the level of everyday experience, The Standardization of Experience reflects on how digital systems subtly shape personal choice and perception.

References

- The Whale and the Reactor

Winner, L. (1986). The Whale and the Reactor. University of Chicago Press.

→ Argues that technologies embody political and social values rather than remaining neutral tools. - The Technological Society

Ellul, J. (1964). The Technological Society. Vintage Books.

→ A classic work asserting that technology develops according to its own internal logic, shaping human society in the process. - The Rise of the Network Society

Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. Blackwell.

→ Analyzes how information and network technologies restructure social organization and power relations. - The Question Concerning Technology

Heidegger, M. (1977). The Question Concerning Technology. Harper & Row.

→ Explores technology as a mode of revealing that shapes how humans understand and relate to the world. - The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs.

→ Critically examines how digital technologies predict, influence, and monetize human behavior.