Why Do People Willingly Queue?

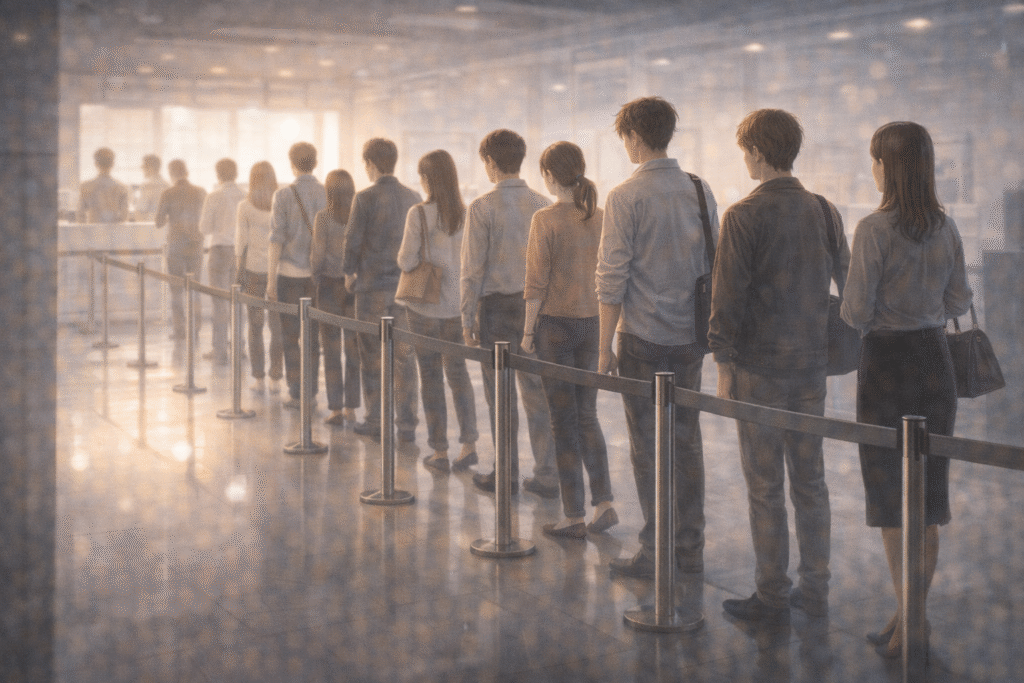

1. Why Do We Line Up So Willingly?

We stand in lines almost every day—

at amusement parks, popular restaurants, hospital counters, and even online shopping platforms where “waiting numbers” appear on our screens.

At first glance, lining up looks like nothing more than inconvenient waiting.

Yet people rarely question it. On the contrary, they often accept it willingly.

Why do we voluntarily endure waiting instead of seeking alternatives?

The answer lies not in patience alone, but in the social meaning embedded in queues.

1.1. Lines as a Guarantee of Fairness

The most fundamental function of a line is fairness.

The rule is simple: first come, first served.

Sociologists describe this as the first-come, first-served norm, a powerful yet easily shared social agreement.

It reassures individuals that their turn will be respected.

If someone cuts the line at a hospital reception desk, frustration spreads immediately.

The anger is not about time alone—it is about the violation of fairness.

Without lines, trust erodes quickly and social conflict intensifies.

2. Waiting Turns Time into Meaning

Interestingly, waiting in line does more than organize order—it reshapes experience.

At amusement parks, waiting two hours for a roller coaster often heightens anticipation.

People feel that the experience must be more rewarding because they invested time.

The same applies to long restaurant lines.

A crowded queue becomes a social signal: this place must be worth it.

Even ordinary food can feel more valuable when framed by a visible line.

3. Lines Create Social Bonds

Standing in line often produces a subtle sense of solidarity.

People waiting for the same goal share space, time, and expectation.

Fans lining up for concert tickets may begin as competitors,

but often end up feeling like comrades.

Small conversations, shared complaints, and mutual understanding emerge.

Lining up is not only about waiting—it is also about belonging.

4. Lines as Tools of Power and Control

Despite their appearance of fairness, lines can also function as instruments of power.

Who controls the line matters.

VIP lanes, priority access, and exclusive queues immediately reveal inequality.

Luxury brands deliberately create long lines to increase perceived value.

Standing in line itself becomes a status symbol—

a sign of inclusion in a desirable group.

In these cases, waiting is no longer neutral; it is carefully designed.

5. Digital Lines in the Online Age

Lines have not disappeared in digital society—they have simply changed form.

Online ticket platforms display messages like “You are number 10,524 in line.”

Video games restrict access with server queues.

Physical waiting has become virtual waiting.

Because digital queues are invisible, trust becomes fragile.

Platforms compensate by showing estimated wait times and live updates,

attempting to preserve the sense of fairness that physical lines once provided.

Related Reading

The politics of everyday space and design are examined in The Politics of Empty Space, where minimalism and structure subtly guide collective behavior.

At a broader social level, the tension between individual freedom and shared order resurfaces in The Minimal State: An Ideal of Liberty or a Neglect of the Common Good?, questioning how fairness is negotiated within structured systems.

Conclusion

Waiting in line is far more than idle time.

It is a social mechanism where fairness, expectation, belonging, and power intersect.

Within the lines we casually join each day,

the hidden order of society quietly reveals itself.

References

- Mann, L. (1969). Queue Culture: The Waiting Line as a Social System.

American Journal of Sociology, 75(3), 340–354.

→ A foundational study analyzing queues as structured social systems that sustain order and fairness. - Schweingruber, D., & Berns, N. (2005). Shaping the Social Experience of Waiting.

Symbolic Interaction, 28(3), 347–367.

→ Examines how theme parks transform waiting into a designed experience of anticipation. - Maister, D. H. (1985). The Psychology of Waiting Lines.

Harvard Business School Service Notes.

→ Explores how perceived fairness and engagement shape satisfaction during waiting.