Liberalism and Social Contract Theory on Trial

1. The Boundary Between Freedom and Power

The state is one of the most powerful institutions humanity has ever created.

It makes laws, guarantees rights, and maintains social order. At the same time, it surveils, regulates, and sometimes legitimizes violence in the name of security. We live under its protection—and under its authority.

This raises a persistent and unsettling question:

Should the state be understood as a guardian of individual freedom, or as a Leviathan that justifies control?

Today’s inquiry stages this question not as a verdict to be delivered, but as a trial of ideas—a stage of reflection where competing philosophies confront one another.

2. The Plaintiff’s Case: The State as Guardian of Freedom

The Liberal Conception of the State

Modern liberal thinkers have long argued that the state exists primarily to protect individual rights.

John Locke, in Two Treatises of Government, maintained that human beings are born free and equal, possessing natural rights to life, liberty, and property. According to this view, the state is a minimal mechanism created solely to secure these rights—not to override them.

John Stuart Mill reinforced this position in On Liberty, insisting that state interference must be kept to an absolute minimum. For Mill, individual autonomy is not merely a private good; it is the engine of social progress. A society flourishes when individuals are free to think, speak, and live according to their own convictions, so long as they do not harm others.

From this perspective, the state resembles a watchful guardian: present, but restrained. It is not a master of citizens, but a protector of their freedom. Contemporary democratic institutions—freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of religion—are often cited as evidence that the liberal vision of the state remains alive.

The plaintiff’s argument is clear: the state’s legitimacy rests on its ability to safeguard freedom, not to manage lives.

3. The Defendant’s Case: The State as Leviathan

Control as a Condition of Order

The opposing view, however, paints a far darker picture of human nature—and a far stronger role for the state.

Thomas Hobbes, in Leviathan, famously described life in the state of nature as a condition of perpetual insecurity: a war of all against all. In such a world, life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

To escape this chaos, individuals enter a social contract, surrendering portions of their freedom to a sovereign authority capable of enforcing order. That authority is the state—powerful, centralized, and uncompromising when necessary.

From this standpoint, the state is not merely a guardian of freedom; it is a mechanism that legitimizes control in order to prevent collapse. Freedom without authority, Hobbes argued, leads not to harmony but to fear.

Modern history offers many examples that echo this logic. During pandemics, governments restrict movement. In the name of security, states monitor borders, communications, and data flows. These actions undeniably limit individual freedom, yet they are often defended as necessary for collective survival.

The defendant’s case insists that control is not the enemy of freedom, but its precondition.

4. Evidence and Counterarguments

The tension between these positions becomes most visible when state power expands.

From the liberal perspective, growing surveillance capabilities—especially in digital societies—pose a serious threat to freedom. When governments collect personal data, monitor online behavior, or justify intrusion through vague security concerns, the boundary between protection and domination begins to blur. History offers many reminders that extraordinary powers, once granted, are rarely surrendered voluntarily.

The defense responds by questioning the feasibility of unrestricted freedom. Absolute liberty, it argues, can undermine the freedom of others. Disinformation, hate speech, and unregulated digital platforms can erode democratic trust and social cohesion. In such cases, state intervention is framed not as oppression, but as a means of preserving the conditions under which freedom can exist.

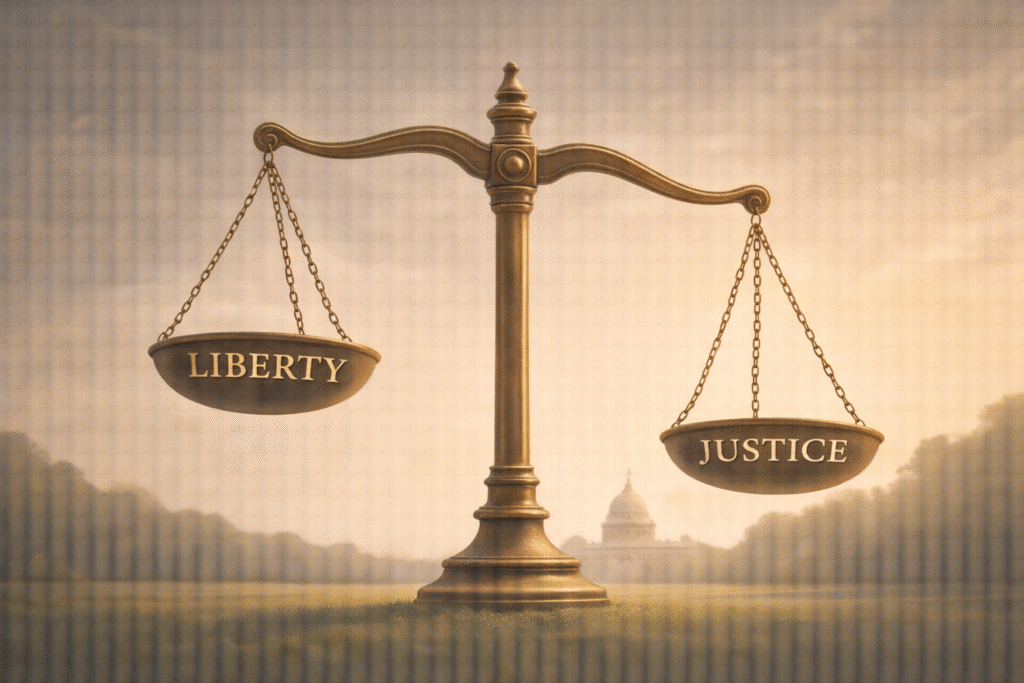

What emerges is not a simple opposition, but a paradox: freedom seems to require both restraint and protection, both limits and guarantees.

5. Contemporary Implications: A Persistent Tension

In practice, modern states embody both roles.

Democratic governments protect civil liberties while simultaneously exercising extensive regulatory and surveillance powers. National security measures restrict privacy. Public health policies limit movement. Data-driven governance promises efficiency but risks turning citizens into transparent subjects.

The state oscillates between guardian and Leviathan, often wearing both masks at once.

As technology advances and crises multiply—climate, health, security—the tension between freedom and control is unlikely to fade. Instead, it will intensify, demanding continual negotiation rather than definitive resolution.

Conclusion: An Unfinished Trial

Is the state a shield that protects our freedom, or a Leviathan that disciplines and controls us?

The plaintiff argues for restraint, warning that unchecked power corrodes liberty. The defense insists that authority is indispensable in an uncertain world. Both present compelling evidence. Neither delivers a final answer.

The courtroom remains open. The verdict is deferred.

Perhaps this question cannot—and should not—be settled once and for all. Instead, it must remain alive, shaping our political choices and institutional designs.

The state stands before us, neither purely protector nor purely monster, but a reflection of how we choose to balance freedom and control.

Related Reading

This political dilemma resonates with deeper questions about moral authority raised in Can Humans Be the Moral Standard?.

Economic assumptions behind freedom and responsibility are also examined in The Illusion of “Free”: How Zero Price Changes Our Decisions.

References

- Hobbes, T. (1651/1996). Leviathan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hobbes presents the state as a powerful sovereign created to escape the chaos of the state of nature. His conception of Leviathan remains foundational for arguments that justify strong authority in the name of order and security. - Locke, J. (1689/1988). Two Treatises of Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Locke articulates the liberal vision of the state as a protector of natural rights. His work forms the philosophical basis for constitutional government and limits on political power. - Mill, J. S. (1859/1977). On Liberty. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Mill defends individual autonomy against state interference, emphasizing freedom as a condition for personal and social development. His arguments remain central to modern liberal thought. - Berlin, I. (1969/2002). Four Essays on Liberty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berlin’s distinction between negative and positive liberty provides a conceptual framework for understanding the tension between freedom and authority in modern political life. - Foucault, M. (1975/1995). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Foucault analyzes how modern states exercise power through surveillance and discipline, revealing how control can expand even within systems that formally endorse freedom.