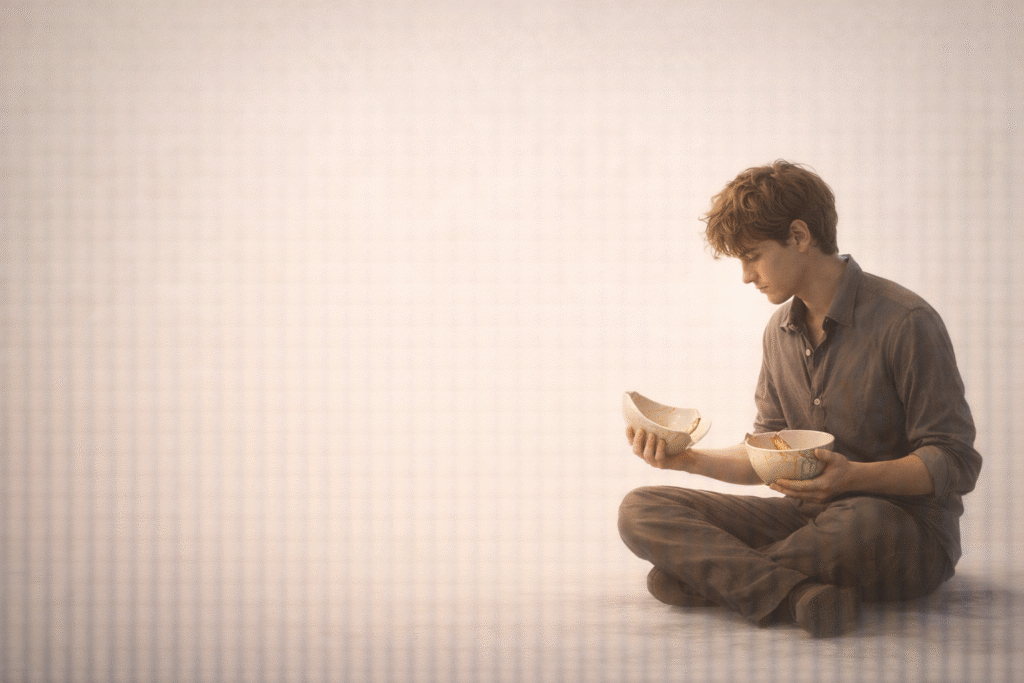

The Endless Tension Between Imperfection and the Desire for Wholeness

Standing in front of a mirror at the start of the day, we often notice small misalignments—

a crooked button, unruly hair, a detail slightly out of place.

They seem trivial, yet they quietly invite a deeper question:

Why can’t I ever be completely right?

Human life is filled with such imperfections.

What is striking, however, is that these flaws rarely end in resignation.

Instead, we continue to imagine better versions of ourselves and strive toward a more complete life.

Perhaps the moment we recognize imperfection is precisely the moment our pursuit of perfection begins.

1. Philosophical Perspectives — Imperfection as an Ontological Trigger

1.1 Lack as the Origin of Aspiration

In Symposium, Plato explains human desire through the concept of lack.

We seek beauty, goodness, and truth not because we possess them, but because we do not.

Imperfection, in this sense, is not a weakness—it is the very condition that gives rise to longing and growth.

Aristotle similarly described humans as rational animals, whose reason enables them to recognize deficiency and move toward excellence (arete).

To be human, then, is not to be complete, but to strive.

1.2 Modern Reflections on Human Fragility

Blaise Pascal famously called humans “thinking reeds.”

We are fragile and finite, yet capable of contemplating infinity.

This paradox—weakness combined with reflection—makes imperfection not merely a flaw, but the source of human dignity.

2. Religious Perspectives — Perfection as an Unreachable Ideal

2.1 Theological Limits of Human Completion

In Christian theology, humans are marked by original sin and cannot achieve perfection without divine grace.

Yet the moral task is not to become perfect, but to move toward holiness.

The value lies in direction, not arrival.

2.2 Spiritual Practice and Acceptance of Limits

Buddhist traditions likewise emphasize human entanglement in ignorance and attachment.

Enlightenment is not achieved by becoming flawless, but by recognizing impermanence and letting go of rigid ideals.

Here, perfection functions as orientation rather than destination.

3. Psychological Perspectives — Perfectionism and Self-Awareness

3.1 The Double Edge of Perfectionism

Psychology describes the tension between imperfection and aspiration through perfectionism.

At its best, perfectionism motivates growth and discipline.

At its worst, it produces anxiety, self-criticism, and chronic dissatisfaction.

3.2 Social Recognition and the Fear of Exposure

Modern research shows that perfectionism is deeply connected to social evaluation.

We are aware of our flaws, yet we fear revealing them to others.

The desire to appear flawless often reflects not self-confidence, but vulnerability.

4. Evolutionary Perspectives — Imperfection as a Survival Strategy

4.1 Biological Limits and Human Innovation

From an evolutionary standpoint, human imperfection has always demanded compensation.

Lacking physical strength or speed, humans developed tools, language, and cooperation.

Our awareness of limitation fueled creativity and adaptation.

4.2 Progress Through Dissatisfaction

The pursuit of “better” weapons, safer shelters, and more accurate knowledge emerged from recognizing what was insufficient.

Perfection, here, is not an illusion—it is a guiding pressure that shaped survival itself.

5. Cultural Perspectives — The Aesthetics of Imperfection

5.1 Celebrating the Incomplete

Some cultures embrace imperfection as beauty.

Japanese wabi-sabi aesthetics find meaning in irregularity and transience, while Renaissance art idealized proportion and harmony.

Each reflects a different response to the same human tension.

5.2 Contemporary Myths of Perfection

In the age of social media, flawless images circulate endlessly.

At the same time, movements emphasizing self-acceptance and authenticity are gaining ground.

Modern culture oscillates between hiding imperfection and reclaiming it.

Conclusion — Moving Toward Perfection Without Denying Imperfection

Humans are imperfect beings who know they are imperfect—and still strive for perfection.

This pursuit may never reach its endpoint.

Yet growth does not depend on arrival, but on movement.

To acknowledge imperfection without abandoning aspiration may be the most human stance of all.

Perfection, then, is not a final state, but a horizon—

one that gives direction, meaning, and momentum to an incomplete life.

References

- Aristotle. (1999). Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by T. Irwin. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

→ This foundational work explores human flourishing (eudaimonia) as a process grounded in recognizing limitations and cultivating virtue through practice. Aristotle’s account highlights how imperfection motivates ethical striving rather than signaling failure. - Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press.

→ Frankl argues that human beings seek meaning precisely within conditions of suffering, finitude, and incompleteness. The book offers a psychological and existential account of how imperfection becomes the ground for purpose rather than despair. - Plato. (2002). Symposium. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

→ In this dialogue, Plato presents desire (eros) as arising from lack, positioning imperfection as the source of humanity’s pursuit of beauty, truth, and goodness. The text provides a classical philosophical foundation for understanding aspiration as rooted in incompleteness. - Pascal, B. (1995). Pensées. Translated by A. J. Krailsheimer. London: Penguin Classics.

→ Pascal famously describes humans as fragile yet reflective beings, emphasizing the paradox of weakness combined with the capacity for infinite thought. His reflections illuminate how imperfection and greatness coexist at the core of human identity. - Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). “Perfectionism in the Self and Social Contexts: Conceptualization, Assessment, and Association with Psychopathology.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470.

→ This influential psychological study distinguishes different forms of perfectionism and examines their emotional and social consequences. It provides empirical insight into how awareness of imperfection can lead either to growth or psychological distress.