— The Psychology of Visual Language

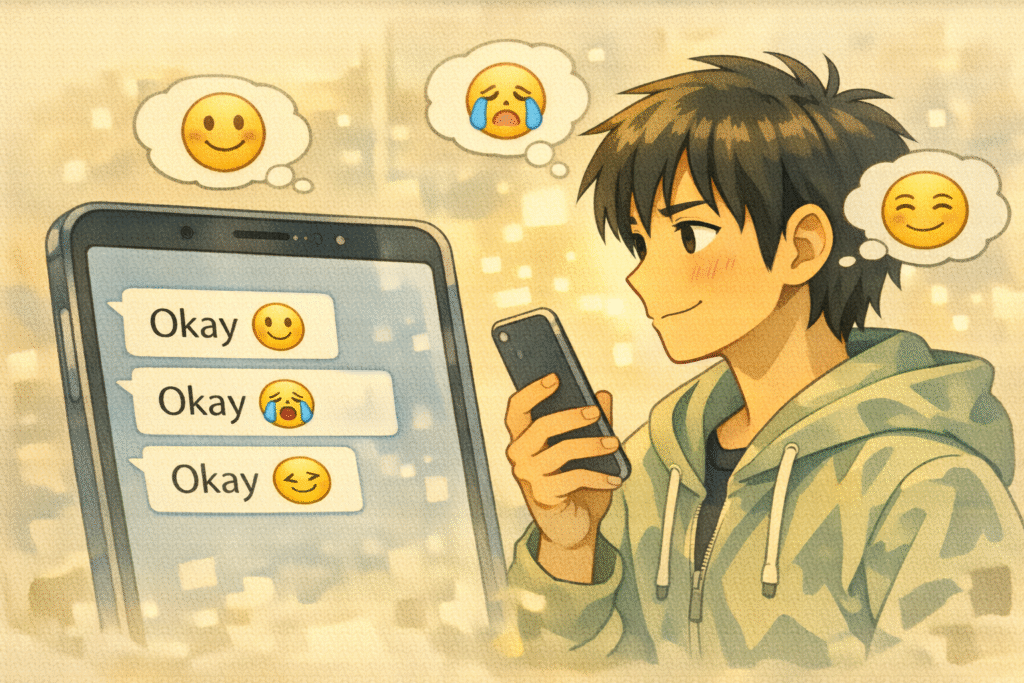

“Okay.”

“Okay 🙂”

“Okay 😭”

The word is the same.

But the feeling changes completely.

In an age where most conversations happen on screens,

emojis are no longer decoration.

They are emotional tools.

Sometimes, a tiny icon communicates more clearly than a full sentence.

So why does a small visual symbol carry such powerful emotional weight?

1. Emojis Replace Lost Facial Expressions

Human communication is deeply nonverbal.

In face-to-face conversations,

tone of voice, facial expression, eye movement, and gestures

all shape meaning.

But digital text strips these cues away.

Emojis step in as substitutes for facial expressions.

🙂 softens a statement.

😅 signals nervous humor.

🙃 suggests irony.

They restore emotional nuance that plain text cannot easily provide.

2. Emojis Compress Emotion Efficiently

Psychology suggests that symbols can compress complex information into simple forms.

Instead of writing:

“I support you even if I cannot say much,”

we might simply send:

💪✨

A single emoji can carry encouragement, warmth, and solidarity.

Emojis allow emotional richness without slowing conversation.

They are efficient containers of feeling.

3. Emojis Clarify Intent

Digital text is highly ambiguous.

“Nice job.”

Is it sincere? Sarcastic? Passive-aggressive?

Add an emoji:

“Nice job 😍” → Genuine praise

“Nice job 😏” → Playful teasing

“Nice job 🤨” → Suspicion

Emojis reduce misinterpretation by signaling intent.

They act as emotional safety devices in fragile digital spaces.

4. Emojis as a Global Emotional Language

Words differ across cultures.

Smiles do not.

😊 👍 ❤️

These symbols transcend linguistic boundaries.

In cross-cultural communication, emojis often bridge emotional gaps faster than translated sentences.

They represent a new shared visual vocabulary of empathy.

Conclusion: A Quiet Evolution of Language

Emojis are not replacing language.

They are expanding it.

They compensate for the emotional limitations of text-based communication.

They make digital interaction warmer, softer, and more human.

Next time you send a message,

ask not only what you want to say,

but how you want it to feel.

Sometimes, a symbol speaks before the sentence does.

Related Reading

The transformation of communication and identity is further explored in The Sociology of Selfies, which investigates how digital expression reshapes social presence.

On a political and structural level, Automation of Politics: Can Democracy Survive AI Governance? considers how algorithmic systems increasingly mediate human interaction and decision-making.

References

1. Evans, V. (2017). The Emoji Code: The Linguistics Behind Smiley Faces and Scaredy Cats. Picador.

→ This book frames emoji as an evolutionary stage of digital language. Evans argues that emoji function as pragmatic emotional markers, restoring tone and nuance lost in text-only communication.

2. Danesi, M. (2016). The Semiotics of Emoji: The Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet. Bloomsbury Academic.

→ Danesi explores emoji through semiotics, showing how visual symbols increasingly operate as meaningful linguistic units rather than decorative elements in digital discourse.

3. Crystal, D. (2008). Txtng: The Gr8 Db8. Oxford University Press.

→ Crystal’s work on digital language provides theoretical grounding for understanding how abbreviated forms, emoticons, and emoji reshape emotional and pragmatic communication online.