Scenes We See Every Day—and Look Away From

Images of war on the news.

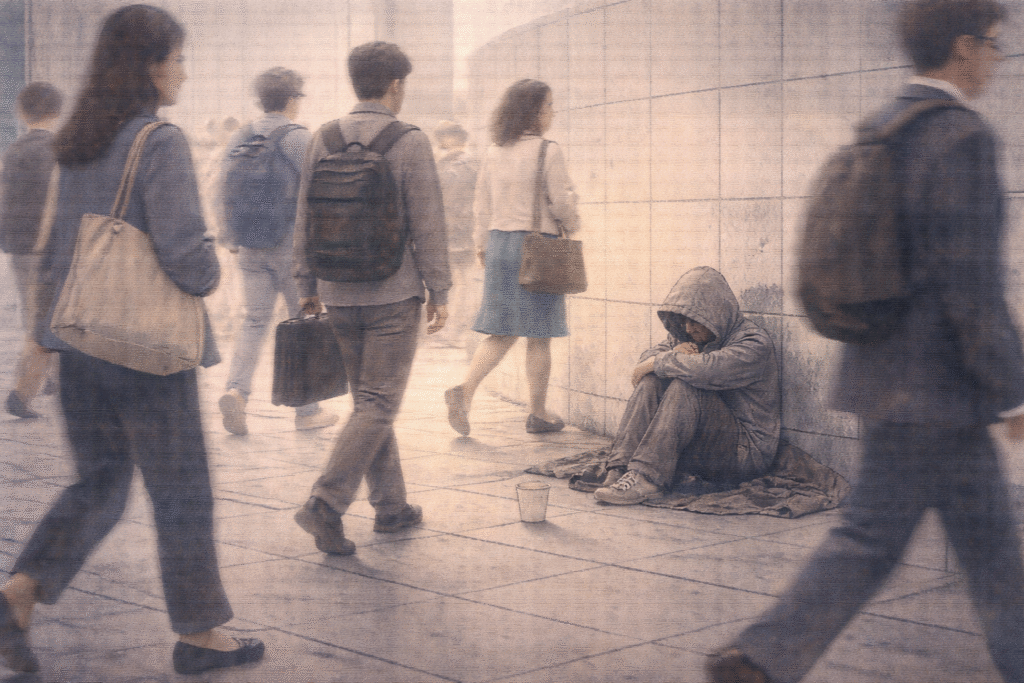

A homeless person shivering in a subway station.

Hate-filled comments flooding online spaces.

We encounter other people’s suffering every day.

Yet most of the time, we scroll past it, avert our eyes, or quietly tell ourselves, “This has nothing to do with me.”

We are taught that humans are empathetic beings.

So why is it that we so often—and so easily—turn away from the pain of others?

1. A Psychological Perspective: Empathy Fatigue and the Bystander Effect

1.1 The Limits of Emotional Capacity

Psychology offers important explanations for why humans cannot absorb others’ suffering indefinitely.

Empathy fatigue refers to the gradual emotional exhaustion that occurs when we are repeatedly exposed to distress.

When news about war, natural disasters, or humanitarian crises arrives daily, initial shock often gives way to numbness. This emotional shutdown is not indifference—it is self-protection.

Another well-documented phenomenon is the bystander effect.

In emergency situations, individuals are less likely to intervene when others are present, assuming that someone else will take responsibility. Ironically, the more witnesses there are, the easier it becomes to do nothing.

1.2 Not Cruelty, but Psychological Structure

In this sense, turning away from suffering is not always a sign of moral failure.

It is often the result of emotional limits and the diffusion of responsibility embedded in human psychology.

2. A Social Perspective: The Normalization and Consumption of Suffering

2.1 When Pain Becomes Information

Modern societies have transformed suffering into consumable content.

Through television, social media, and online news, images of violence, disaster, and tragedy circulate endlessly. Over time, suffering loses its exceptional status and becomes part of the everyday visual landscape.

At the same time, not all suffering receives equal attention.

Disasters in wealthy or geopolitically central regions may dominate headlines, while prolonged crises in poorer parts of the world are reduced to brief mentions—or ignored entirely.

2.2 Hierarchies of Compassion

As a result, suffering becomes ranked and filtered.

Some lives are framed as urgent and grievable, while others fade into the background noise of global information flows.

This selective visibility shapes not only what we see, but also what we feel compelled to care about.

3. An Ethical Perspective: The Face of the Other and Moral Responsibility

3.1 The Ethical Call of the Other

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas argued that the face of the other makes an ethical demand upon us.

To encounter another person’s vulnerability is to be called into responsibility—even before we choose it.

In theory, this means that suffering cannot be morally neutral.

To see pain is already to be implicated in it.

3.2 The Desire to Avoid Responsibility

In practice, however, responding to suffering often requires action.

Looking at a homeless person may lead to the expectation of giving money or food.

Acknowledging social injustice may demand protest, solidarity, or political engagement.

Turning away, then, can function as a way to avoid responsibility.

By not seeing, we protect ourselves from the burden of having to respond.

4. The Contemporary Context: Empathy and Cynicism in the Digital Age

4.1 Expanded Awareness, Diluted Action

Digital platforms have radically expanded our exposure to others’ pain.

Hashtag campaigns, viral videos, and online petitions allow millions to express concern instantly. Yet this visibility does not always translate into sustained action or structural change.

In many cases, digital empathy becomes a momentary emotional release rather than a commitment.

4.2 From Compassion to Cynicism

At the same time, online spaces often foster cynicism and hostility.

Suffering is mocked, politicized, or dismissed as self-inflicted. Comment sections turn pain into ammunition for ideological battles.

The digital sphere thus becomes both a site of expanded empathy and a space where suffering is easily trivialized or denied.

Conclusion: Turning Away—and Turning Back

We turn away from others’ suffering for many reasons:

psychological limits, social structures, ethical avoidance, and digital cultures that reward distance over responsibility.

But looking away does not make suffering disappear.

To face another’s pain is uncomfortable. It can disrupt our sense of safety and challenge our routines. Yet this discomfort is not a flaw—it is the foundation of ethical life.

When we refuse to look away, suffering ceases to be a private misfortune and becomes a shared social concern.

In that moment, we move closer to becoming more connected, more responsible, and more fully human.

Related Reading

Moral responsibility and the limits of ethical judgment are questioned in Can Humans Be the Moral Standard?

Everyday habits that normalize emotional distance are explored in The Wall of Earphones – Why Do We Choose to Isolate Ourselves?

References

- Altruism in Humans

Batson, C. D. (2011). Altruism in Humans. Oxford University Press.

This work provides a comprehensive psychological account of altruism and empathy, explaining why humans sometimes help others and sometimes withdraw. - Against Empathy

Bloom, P. (2016). Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion. Ecco/HarperCollins.

Bloom challenges the assumption that empathy is always morally beneficial, arguing that it can lead to bias, fatigue, and selective concern. - The Psychology of Good and Evil

Staub, E. (2003). The Psychology of Good and Evil. Cambridge University Press.

This book analyzes how individuals and groups come to help or harm others, with particular attention to bystander behavior and moral disengagement. - Totality and Infinity

Levinas, E. (1969). Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Duquesne University Press.

A foundational philosophical text that frames ethics as arising from responsibility to the Other, especially in the face of vulnerability. - The Spectatorship of Suffering

Chouliaraki, L. (2006). The Spectatorship of Suffering. Sage Publications.

This sociological study examines how media representations of suffering shape public response, compassion, and indifference.