A question raised in the age of efficiency

Global temperatures are not the only thing rising in modern society—so are working hours, performance pressure, and expectations of constant availability.

In this context, sleep is no longer taken for granted. It is measured, optimized, shortened, and often sacrificed.

This raises a fundamental question:

Is sleep a natural human right, or merely a tool for maximizing productivity?

This tension is not new. More than a century ago, the Swiss philosopher and legal scholar Karl Hilty (1833–1909) warned against a life dominated by relentless activity and efficiency. His reflections on sleep offer a powerful lens through which to examine our present condition.

1. Karl Hilty and the philosophical meaning of sleep

1.1 Sleep as a foundation of moral life

Karl Hilty, best known for his writings on happiness and practical wisdom, believed that a meaningful life begins with respecting fundamental human needs.

For him, sleep was not a mere biological function. It was a moral and spiritual necessity.

Hilty argued that without sufficient rest, human beings lose emotional balance, ethical clarity, and inner freedom. Fatigue, in his view, dulls moral judgment and erodes character.

1.2 A growing tension in modern society

In contrast, contemporary society treats sleep as something to be managed rather than respected.

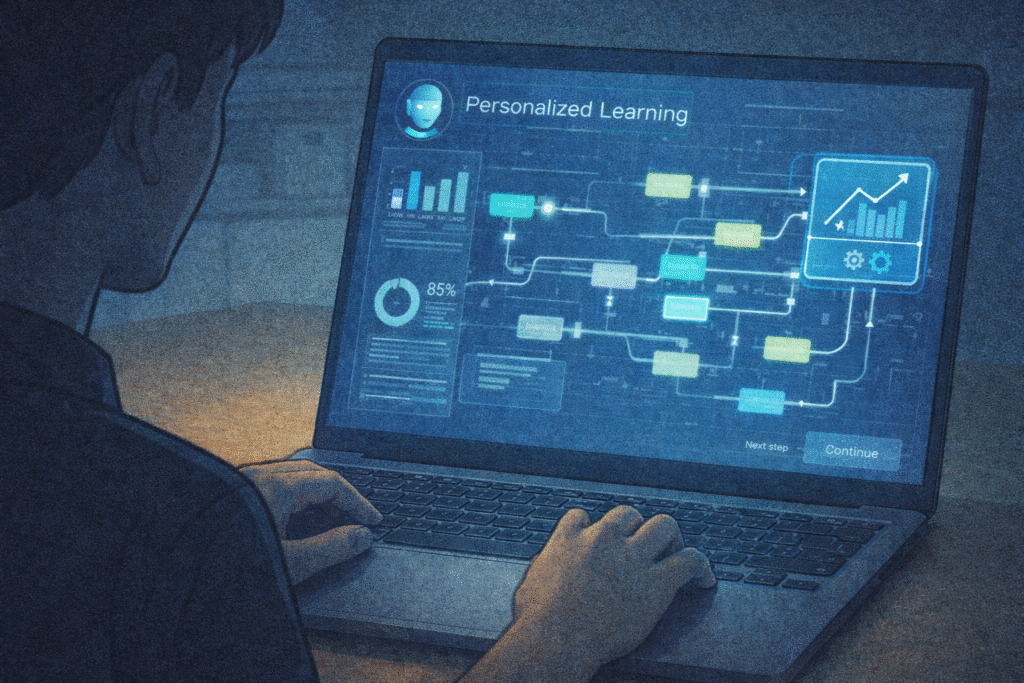

Smartwatches track sleep cycles, apps quantify sleep quality, and individuals are encouraged to function on minimal rest while maintaining peak performance.

In this shift, sleep becomes caught between two competing interpretations:

- a natural human right, or

- a resource to be optimized for productivity.

2. Hilty’s position: Sleep as a natural right

Hilty famously described sleep as “one of God’s greatest gifts to humanity.”

This perspective frames sleep not as indulgence, but as an essential condition for a dignified human life.

2.1 Physical and psychological restoration

Adequate sleep restores both body and mind.

Hilty warned that chronic sleep deprivation leads not only to physical illness but also to irritability, poor judgment, and ethical decline.

2.2 Inner peace and spiritual balance

For Hilty, nighttime rest allowed the human soul to regain equilibrium. Sleep prepared individuals for reflection, self-control, and moral responsibility.

2.3 An inalienable human right

From this standpoint, sleep cannot be subordinated to economic or social demands.

It is a natural right, inseparable from human dignity and therefore not subject to negotiation.

3. The modern view: Sleep as a tool of productivity

In contemporary capitalist societies, however, sleep is increasingly framed as a variable to be controlled.

3.1 The ideology of performance

Popular narratives suggest that “successful people sleep less.”

Wakefulness is celebrated as discipline, while sleep is portrayed as inefficiency.

This logic transforms sleep into a sacrifice rather than a right.

3.2 The rise of the sleep industry

Ironically, as sleep is shortened, it has also become commodified.

Sleep medications, tracking devices, and optimization programs turn rest into a marketable product—one that must be purchased back.

3.3 Self-optimization culture

Morning routines, productivity hacks, and biohacking trends reinforce the idea that sleep exists primarily to fuel work.

Rest becomes valuable only insofar as it enhances output.

4. The core conflict: Right versus instrument

At the heart of this debate lies a philosophical clash:

- Rights-based view:

Sleep is essential to moral agency, mental health, and human dignity. - Instrumental view:

Sleep is a means to economic efficiency and personal achievement.

The question is unavoidable:

Do we respect sleep as part of what it means to be human, or do we treat it as a tool to be engineered?

5. Contemporary implications

5.1 Sleep as a social responsibility

Organizations such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) warn that chronic sleep deprivation violates basic human rights.

Long working hours and insufficient rest are increasingly recognized as structural, not individual, problems.

5.2 The need for balance

Productivity cannot be ignored. Yet reducing human beings to machines optimized for output risks erasing what makes life meaningful.

5.3 Hilty’s enduring question

Hilty’s philosophy leaves us with a profound inquiry:

Do we sleep merely to work better tomorrow, or to live more deeply today?

Conclusion: Sleep at the crossroads of humanity

Karl Hilty’s reflections remind us that sleep is not a luxury, nor a weakness.

It is a cornerstone of ethical life and inner freedom.

Modern society, however, increasingly treats sleep as a tool to be managed in service of productivity.

The question therefore remains open—and urgent:

Is sleep a fundamental human right, or a resource to be optimized?

How we answer this question will shape not only our sleeping habits, but our understanding of what it means to be human.

Related Reading

The culture of acceleration and digital exhaustion is analyzed in Digital Aging: When Technology Moves Faster Than We Do, reflecting on how technological tempo alters human rhythms.

The existential dimension of rest and reflection emerges in A Night Sky Narrative — A Quiet Story Told by Starlight, where slowing down becomes a philosophical act.

References

- Hilty, K. (1901/2002). Happiness: Essays on the Meaning of Life. Kessinger Publishing.

→ A foundational text outlining Hilty’s philosophy of simplicity, rest, and moral life, offering deep insight into his view of sleep as a human necessity. - Williams, S. J. (2011). Sleep and Society: Sociological Ventures into the (Un)known. Routledge.

→ Examines sleep as a social and cultural phenomenon, exploring its transformation from a private need into a managed social practice. - Wolf-Meyer, M. J. (2012). The Slumbering Masses: Sleep, Medicine, and Modern American Life. University of Minnesota Press.

→ Analyzes how sleep has become medicalized and regulated in modern society, contrasting sharply with humanistic perspectives like Hilty’s. - Kushida, C. A. (Ed.). (2007). Sleep Deprivation: Clinical Issues, Pharmacology, and Sleep Loss Effects. CRC Press.

→ Provides scientific evidence on the physical and psychological consequences of sleep deprivation, supporting arguments for sleep as a fundamental right. - Crary, J. (2013). 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. Verso Books.

→ A critical examination of how late capitalism erodes sleep, framing rest as one of the last frontiers of resistance against total productivity.