The World We Enter Each Night

Every night, we step into the strange and familiar world of dreams.

Some nights, nothing remains in our memory. On others, a single dream lingers, quietly shaping our thoughts throughout the day.

What is fascinating is that the same dream can be interpreted very differently across cultures.

In one society, it may signal good fortune; in another, it may be read as a warning or an omen.

How, then, have human societies interpreted dreams?

And what do these cultural differences reveal about the ways we understand ourselves and the world?

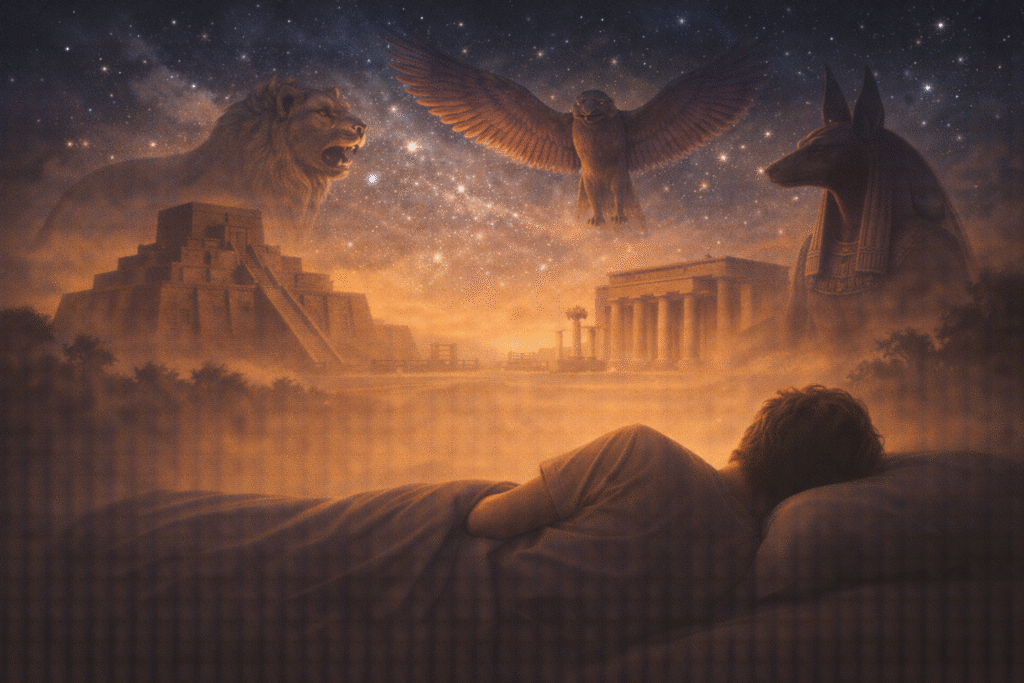

1. When Dreams Were Messages from the Divine

In many ancient societies, dreams were not considered mere psychological events. They were believed to be messages sent by gods, ancestors, or natural forces.

In ancient Mesopotamia, dream interpretation was so significant that professional dream interpreters existed. In Egypt, the dreams of pharaohs were sometimes treated as divine revelations capable of shaping the fate of the entire kingdom.

The Epic of Gilgamesh repeatedly portrays characters who dream and then act upon the interpretations of those dreams. In this worldview, dreams served as a bridge between the human and the divine—a channel through which invisible forces communicated with mortals.

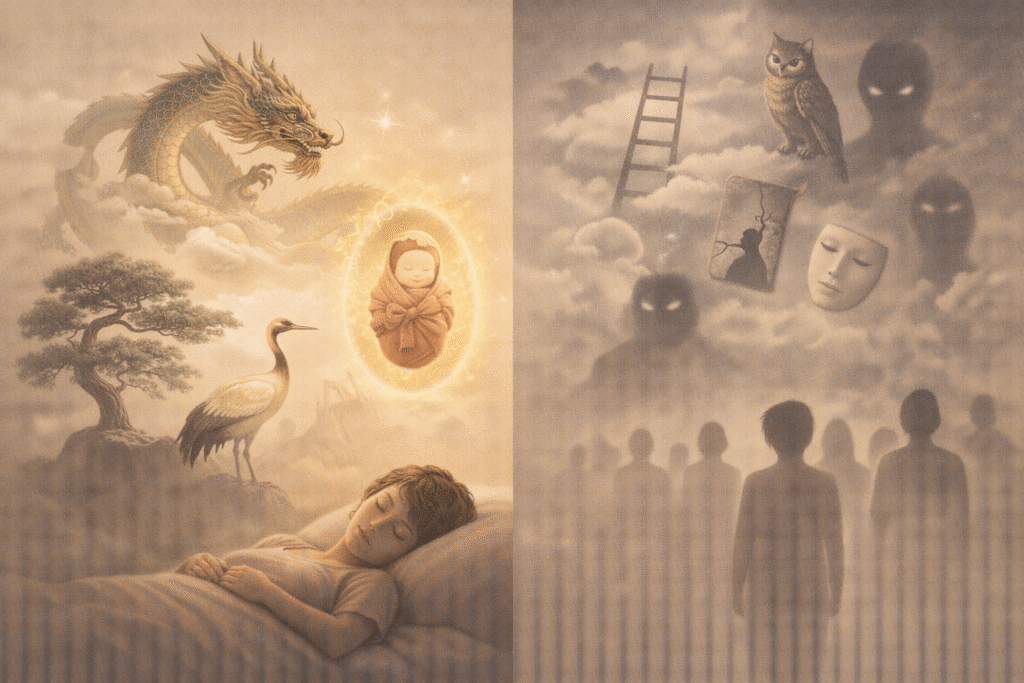

2. Eastern Perspectives: Harmony and Cycles

In many East Asian traditions, dreams were interpreted through a more holistic and cyclical understanding of life.

In Korea, China, and Japan, taemong—dreams surrounding conception and pregnancy—have long been considered meaningful signs. Such dreams are believed to hint at a child’s character, destiny, or fortune.

Traditional interpretations often link animals and natural symbols to future outcomes: dragons or tigers may signal the birth of a strong son, while flowers or fruits may suggest a daughter. Within Confucian cultural contexts, dreams were also understood as reflections of the flow of qi (vital energy), revealing the dreamer’s emotional and moral state.

Rather than isolating dreams as irrational phenomena, Eastern traditions often integrated them into broader systems of harmony between nature, society, and the self.

3. Western Thought: Dreams as the Language of the Unconscious

In the late nineteenth century, Western dream interpretation underwent a dramatic transformation.

Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams reframed dreams as expressions of the unconscious mind. According to Freud, dreams symbolized repressed desires and unresolved psychological conflicts. Falling dreams, for example, could represent anxiety or a loss of control, while other symbols pointed to hidden fears or forbidden wishes.

Carl Jung later expanded this view, arguing that dreams were not merely personal but connected to the collective unconscious. For Jung, dream symbols guided individuals toward psychological integration and self-realization.

In modern Western thought, dreams thus became tools for understanding the inner architecture of the mind rather than messages from external divine forces.

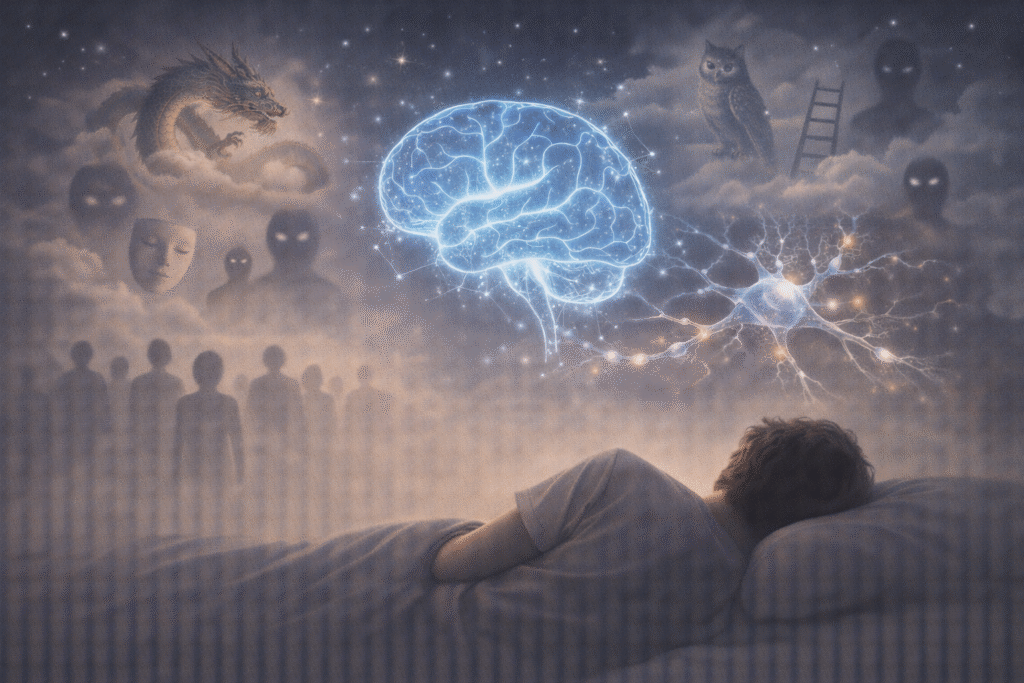

4. Dreams Today: Between Science and Culture

In contemporary society, dreams are also studied through neuroscience. Research shows that dreams most commonly occur during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep and play a role in memory consolidation and emotional regulation.

Yet culture continues to shape how dreams are understood.

In parts of Latin America, dreams are still believed to involve communication with ancestral spirits. In some African communities, dreams guide communal rituals and collective decision-making. Even in modern Korea, traditional interpretations—such as the belief that dreaming of pigs signals financial luck—remain deeply embedded in everyday life.

Despite scientific explanations, cultural meaning has not disappeared. Instead, it coexists with biological accounts of dreaming.

5. Conclusion: Dreams as Cultural Mirrors

Dreams lie beyond our conscious control, yet they reflect the cultural frameworks through which we interpret experience.

The same dream can be fortunate or ominous, meaningful or meaningless, depending on cultural context. These differences are not trivial variations in folklore but windows into how societies understand reality, fate, and the self.

Dreams continue to ask us enduring questions:

Why did I dream this?

And how should I understand what it means?

In answering them, we are not merely interpreting dreams—we are interpreting ourselves.

References

Related Reading

The human longing for meaning beyond immediate reality continues in Dreams, Utopia, and the Impossible.

These symbolic interpretations also echo cultural hierarchies questioned in Civilization and the “Savage Mind”: Relative Difference or Absolute Hierarchy?

- Freud, S. (1899). The Interpretation of Dreams.

→ A foundational text in psychoanalysis that established dreams as expressions of the unconscious, shaping modern Western approaches to dream interpretation. - Bulkeley, K. (2008). Dreaming in the World’s Religions: A Comparative History.

→ A comprehensive cultural history examining how dreams function within major religious and cultural traditions worldwide. - Oppenheim, A. L. (1956). The Interpretation of Dreams in the Ancient Near East.

→ A classic scholarly work on dream interpretation in Mesopotamian civilization, including early dream manuals and religious symbolism.