Travel, Hobbies, and the Rise of Experiential Capital

We no longer ask, “Did you enjoy your trip?”

We ask, “Where have you been?”

We no longer ask, “Do you like your hobby?”

We ask, “How good are you at it?”

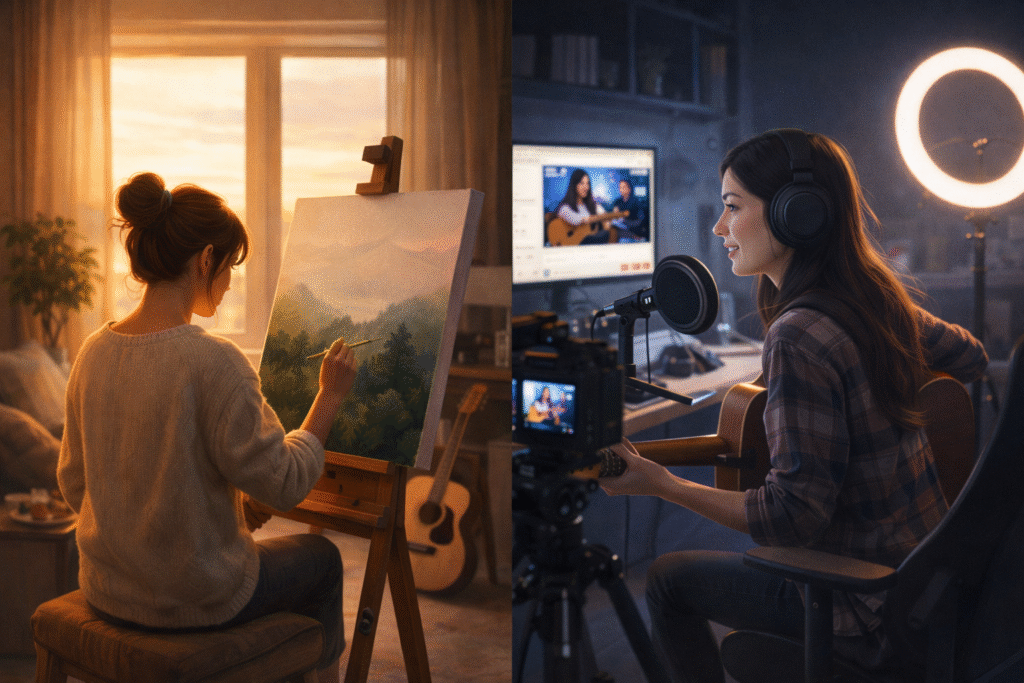

Somewhere along the way, experience stopped being something we felt and became something we performed. What once belonged to memory now belongs to visibility.

This shift is not simply psychological. It is sociological.

1. From Cultural Capital to Experiential Capital

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued that society is structured not only by economic capital, but also by cultural capital — taste, education, manners, aesthetic preferences.

Today, we might add another layer: experiential capital.

- The countries you have visited

- The art exhibitions you have attended

- The lifestyle activities you practice

- The stories you can tell

Experiences increasingly function as social signals. They communicate mobility, refinement, exposure, or privilege.

Travel destinations, hobbies, and lifestyle choices appear personal. Yet they often reflect structural access to time, resources, and networks.

Experience becomes symbolic currency.

2. The Experience Society

German sociologist Gerhard Schulze described modern Western societies as an “experience society” (Erlebnisgesellschaft).

In earlier eras, survival and stability defined a good life.

Today, intensity and uniqueness define it.

A meaningful life is no longer one that is secure, but one that is rich in experiences.

But when experience becomes central to identity, it also becomes competitive.

Ordinary moments are rarely shared.

Moderate experiences rarely trend.

Subtle satisfaction rarely goes viral.

Platforms amplify what is exceptional, spectacular, or emotionally intense.

Gradually, we internalize this logic.

We do not simply experience life.

We curate it.

3. The Platform Effect: Visibility and Comparison

Social media has not created comparison, but it has industrialized it.

Experiences are quantified:

- Followers

- Likes

- Views

- Places visited

- Certifications earned

Numbers appear neutral.

But they quietly produce hierarchy.

We compare our everyday reality with someone else’s highlight reel.

The more visible experiences become, the harder satisfaction becomes.

4. The Marketization of Feeling

In the experience economy, what is sold is not a product but a feeling.

“Authentic travel.”

“Transformative retreat.”

“Elite hobbyist culture.”

Emotion becomes designed, packaged, and sold.

This is where Bourdieu and Schulze meet:

Experiences are both cultural capital and emotional commodities.

We do not just consume goods.

We consume identities.

5. What Are We Losing?

When experience becomes capital, depth can be replaced by accumulation.

We visit more places but stay less deeply.

We try more hobbies but master fewer.

We share more moments but inhabit fewer.

The competition for intensity produces quiet anxiety:

Am I living fully enough?

Yet the anxiety may not come from personal failure,

but from structural comparison.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Experience as Presence

Understanding the structure changes the question.

Instead of asking:

- Is my experience impressive enough?

We might ask:

- Is it meaningful to me?

- Would it matter if no one saw it?

- Does it deepen me, or merely display me?

Experience does not have to function as capital.

It can return to what it originally was:

a lived sensation, not a performed asset.

Perhaps the rarest luxury today is not an exotic destination,

but an unshared moment.

When comparison pauses, experience becomes personal again.

And when experience becomes personal,

it stops being competition.

Related Reading

The psychology behind curated lifestyles and digital self-presentation is further explored in The Standardization of Experience — How Modern Systems Shape Everyday Life, where personal moments gradually become structured performances within invisible social frameworks.

At a deeper technological and existential level, the transformation of human identity under algorithmic influence is examined in AI Beauty Standards and Human Diversity — Does Algorithmic Beauty Threaten Us?, where digital norms begin to redefine what it means to be human.

References

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Harvard University Press.

→ Bourdieu demonstrates that taste and lifestyle choices are socially structured rather than purely individual. His concept of cultural capital explains how travel, hobbies, and aesthetic experiences function as markers of social distinction, making “experience” a form of symbolic capital in modern societies. - Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business School Press.

→ Pine and Gilmore argue that advanced economies increasingly sell memorable experiences rather than goods or services. Their framework clarifies how emotions and staged experiences become economic commodities within contemporary consumer culture. - Schulze, G. (1992). Die Erlebnisgesellschaft: Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart. Campus Verlag.

→ Schulze introduces the idea of the “experience society,” in which individuals pursue intensity, uniqueness, and emotional stimulation as central life goals. His analysis helps explain the cultural shift from stability-oriented values to experience-driven identity formation. - Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140.

→ Festinger’s foundational theory explains how individuals evaluate themselves through comparison with others. In digital environments, this mechanism becomes amplified as experiences are constantly visible and quantifiable. - Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

→ Goffman conceptualizes everyday interaction as a form of performance. His dramaturgical framework offers a powerful lens for interpreting social media culture, where experiences are curated and identities are staged before an imagined audience.