The Collective Meaning of Covering the Face

1. Masks Call Forth “Another Self”

When a person puts on a mask, a subtle transformation begins.

The act does not simply conceal the face; it alters how one relates to oneself and to others.

Masks are not merely tools for hiding the face. From ancient tribal societies to contemporary festivals, they have functioned as cultural instruments through which humans temporarily set aside their ordinary identities while simultaneously stepping into something new. Through masks, people cross the boundaries of everyday life and enter shared spaces of collective energy, emotion, and cultural meaning.

1.1 Stepping Away from the Everyday Self

At the moment a mask is worn, individuals become partially detached from their daily social roles.

Words and behaviors that would normally feel restrained or inappropriate suddenly become permissible.

During the Venetian Carnival, for instance, masks erased visible distinctions between nobles and commoners. Social rank was suspended, allowing participants to interact under temporarily equal conditions. Behind the mask, individuals were no longer defined by status but by participation in a collective festive experience.

1.2 Temporary Identities and Hidden Desires

By stepping away from fixed social roles,

individuals acquire temporary identities.

This is not mere play.

It reveals a deeply human desire for alternative selves—

the urge to explore identities suppressed by everyday norms.

2. Masks Generate Collective Energy

2.1 From Individuals to Symbols

Masks amplify power beyond the individual.

In many African traditional festivals, masks represent ancestral spirits or natural forces.

Those who wear them are no longer seen as private individuals,

but as symbolic embodiments of the community itself.

Through masks, the festival becomes a shared ritual

in which collective memory and emotion are activated.

2.2 Masks and Social Expression in Korea

Korean talchum (mask dance) offers a similar example.

Through exaggerated masks of aristocrats, monks, and servants,

performers express satire, resentment, and hope shared by the community.

The mask becomes a voice for collective feeling.

3. Masks as Tools for Crossing Boundaries

3.1 Reversing Social Order

Festival masks temporarily overturn social hierarchies.

Desires normally restrained,

mockery of authority,

and critique of power structures

are permitted behind the mask.

3.2 Ritualized Disorder and Social Release

During medieval Europe’s Fête des Fous (Festival of Fools),

commoners dressed as clergy and filled churches with laughter and satire.

This was not mere chaos.

It functioned as a release valve, easing social tension

before ordinary order was restored.

Masks, then, serve as keys—

unlocking the boundary between order and disorder,

the everyday and the extraordinary.

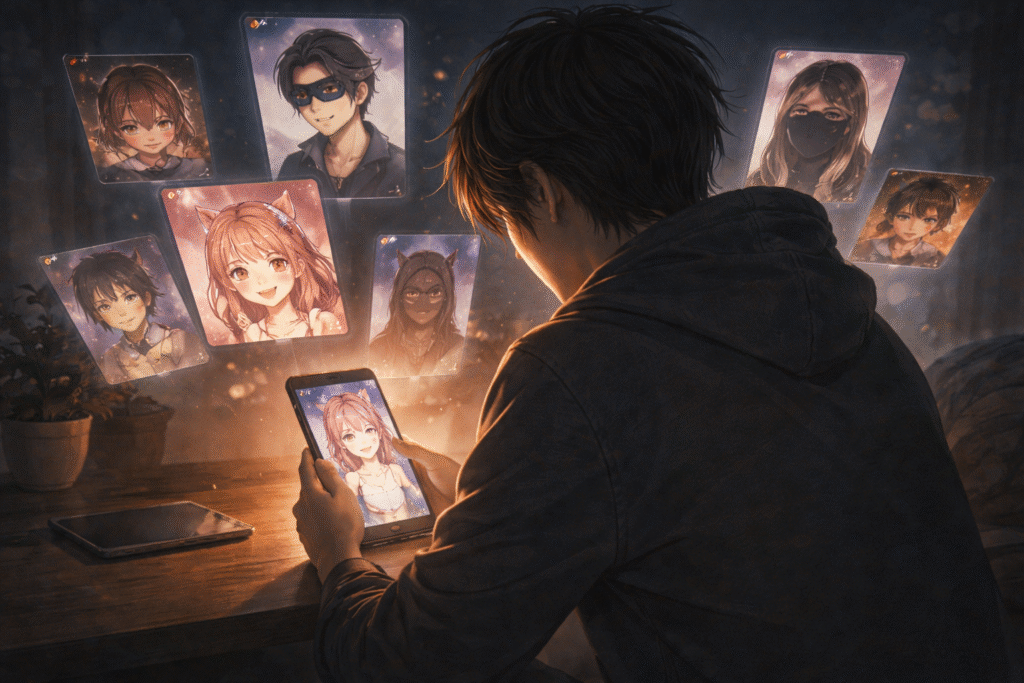

4. Modern Masks: Digital Personas

4.1 Contemporary Forms of Masking

Even today, masks have not disappeared.

Online avatars, profile photos, and usernames

are modern forms of masking.

They allow individuals to hide their physical faces

while communicating through constructed identities.

4.2 Freedom and Its Shadows

Digital masks can offer freedom and creativity.

Yet they also carry risks.

Unlike festival masks that bind communities together,

digital anonymity can sometimes foster hostility,

collective aggression, or hate speech.

The social power of masks remains—

but its direction has changed.

5. The Lesson of Masks: Balancing Concealment and Revelation

5.1 Hiding in Order to Reveal

Masks conceal the face,

but they reveal suppressed desires and collective messages.

They show how societies release tension,

redefine relationships,

and sustain culture across generations.

5.2 From Festivals to Digital Space

In festivals, masks symbolized liberation and shared joy.

In digital spaces, they represent new modes of interaction.

The challenge today is recognizing the collective meanings masks produce—

and deciding how to use them constructively.

6. Conclusion

Masks are not decorative objects.

They are mirrors reflecting human desire and social relationships.

Festival masks allowed people to step beyond everyday constraints

and experience the strength of communal life.

Today, we continue to wear masks in new forms.

What matters is how we balance the freedom masks provide

with the responsibility they demand.

References

- Eliade, M. (1958). Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth. New York: Harper & Row.

Eliade explains how masks function within rites of passage, revealing their role as symbolic tools in collective transformation and rebirth. - Schechner, R. (2003). Performance Theory. New York: Routledge.

A foundational work in performance studies, analyzing how masks in ritual, theater, and festivals restructure social roles and generate collective energy. - Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine.

Turner theorizes how festivals and rituals, often involving masks, temporarily invert social order to create shared communal experience.