— Understanding the Actor–Observer Bias

When I make a mistake,

“I had a good reason.”

When someone else makes the same mistake,

“What’s wrong with them?”

Have you noticed this pattern?

If someone cuts in traffic, we feel anger.

But when we cut in because we are late,

we expect understanding.

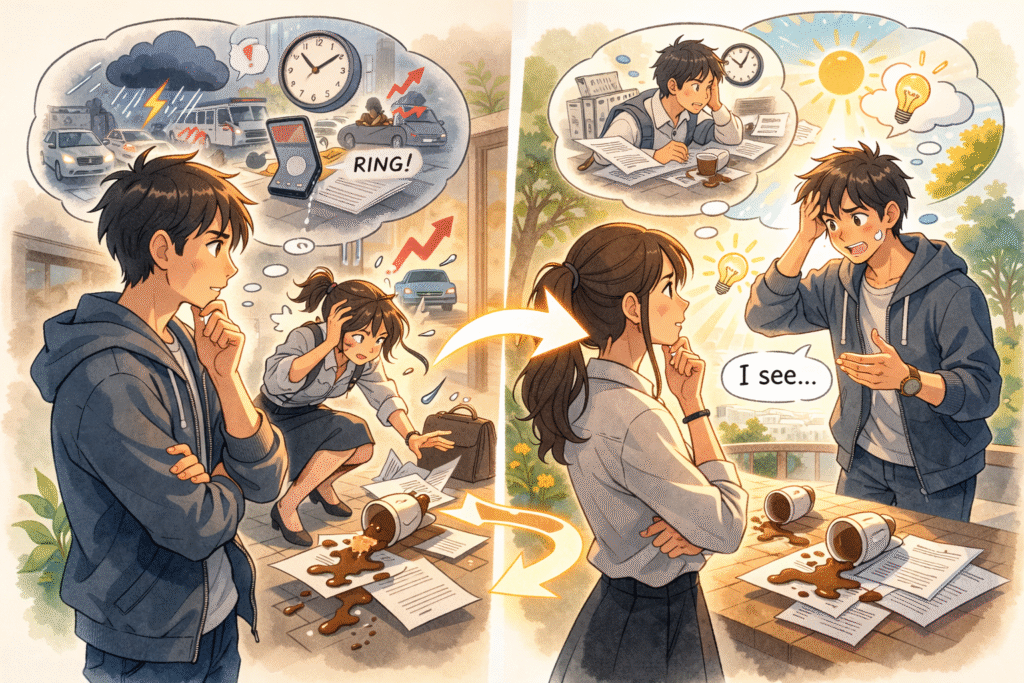

This common psychological tendency is known as the Actor–Observer Bias.

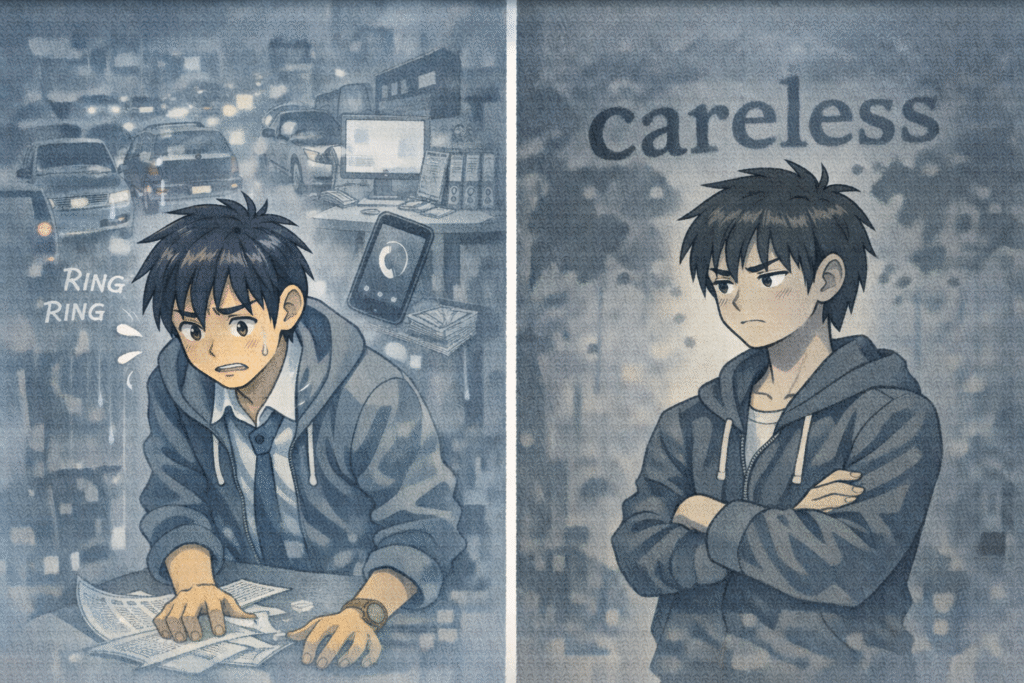

1. My Behavior Is Situational. Yours Is Personal.

The concept was introduced by Edward Jones and Richard Nisbett in the 1970s.

The idea is simple:

When I fail → It was the situation.

When you fail → It was your personality.

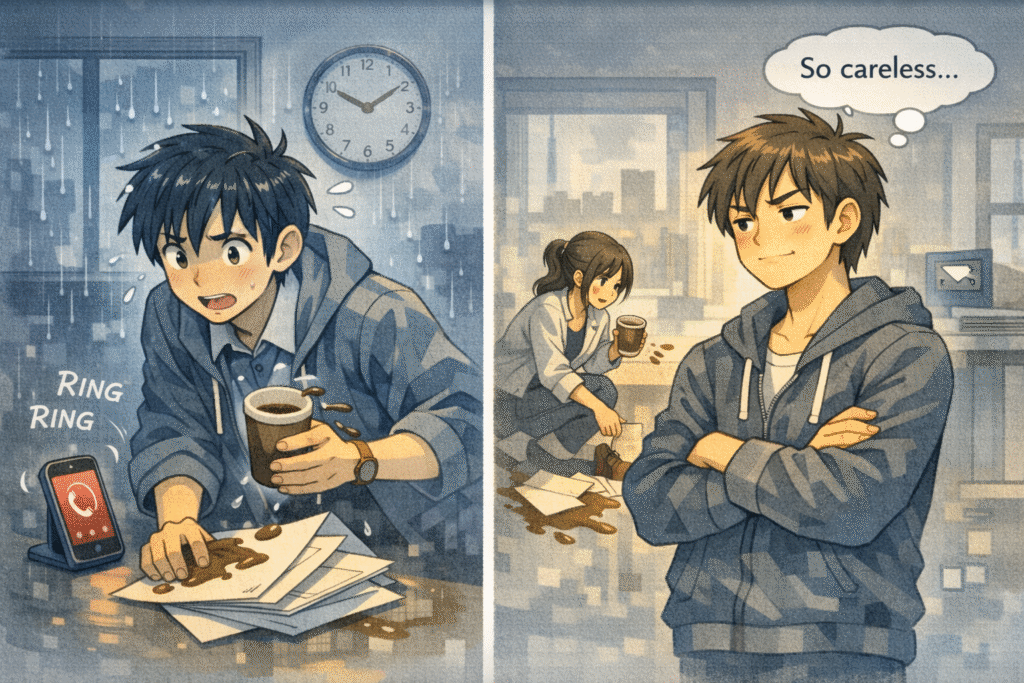

If I miss a deadline,

“I was overwhelmed.”

If you miss a deadline,

“You’re irresponsible.”

As actors in our own lives, we see context.

As observers of others, we see character.

2. The Power of Perspective

This bias stems from point of view.

When I act, I know what I was feeling,

what constraints I faced,

what pressure I experienced.

When I observe you,

I see only the visible behavior.

My inner world is vivid to me.

Yours is invisible.

That asymmetry creates distorted judgment.

3. Why It Damages Relationships

The bias becomes sharper in close relationships.

If I respond late:

“I had a stressful day.”

If you respond late:

“You don’t care anymore.”

We interpret our own behavior through circumstance,

but others’ behavior through intention.

Over time, this pattern breeds misunderstanding and resentment.

4. How to Reduce the Bias

Awareness is the first step.

Before judging, try asking:

“What situation might they be in?”

“Would I act differently under the same pressure?”

Switching perspective softens attribution.

Replacing

“Why are they like that?”

with

“What might have happened?”

can transform conflict into understanding.

Conclusion

We see ourselves in full color and others in outline.

The Actor–Observer Bias is not a flaw of bad character.

It is a built-in feature of human cognition.

But once we recognize it,

we gain a choice.

A choice to pause.

A choice to interpret more gently.

A choice to understand before blaming.

Sometimes, empathy begins with changing the angle of view.

Related Reading

The psychological roots of self-perception and social comparison are further explored in The Sociology of Selfies, where identity and recognition are analyzed in digital contexts.

From a structural perspective, The Age of Overexposure: Why Do We Turn Ourselves into Products? expands this discussion by questioning how social systems amplify performative identity.

References

1. Jones, E. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (1972). The Actor and the Observer: Divergent Perceptions of the Causes of Behavior. In Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behavior.

→ This foundational work formally introduced the actor–observer bias and demonstrated how individuals attribute their own actions to situational factors while attributing others’ actions to personality traits.

2. Ross, L. (1977). The Intuitive Psychologist and His Shortcomings. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology.

→ Ross developed the concept of the fundamental attribution error, closely related to the actor–observer bias, highlighting how people underestimate situational influences when judging others.

3. Gilbert, D. T. (1998). Ordinary Personology. In The Handbook of Social Psychology.

→ Gilbert explains how everyday people form quick judgments about others and why attribution biases persist even when we attempt to be objective.