The Ethics and Controversies of Artificial Wombs

1. What Is an Artificial Womb?

Technology Crossing the Boundary of Life

An artificial womb (ectogenesis) is a system designed to sustain embryonic or fetal development outside the human body, reproducing essential physiological functions such as oxygen exchange and nutrient delivery.

Once considered a miracle of nature, human birth is now approaching a technological threshold.

Recent experiments in Japan and the United States have sustained animal fetuses in artificial wombs, raising the possibility that gestation may no longer be confined to the human body. While researchers emphasize medical benefits—especially for extremely premature infants—this shift introduces a deeper ethical question:

If human life can begin in a laboratory, who—or what—decides that life should exist?

This question signals a transformation of birth itself—from a biological event to a social, ethical, and political decision shaped by technology.

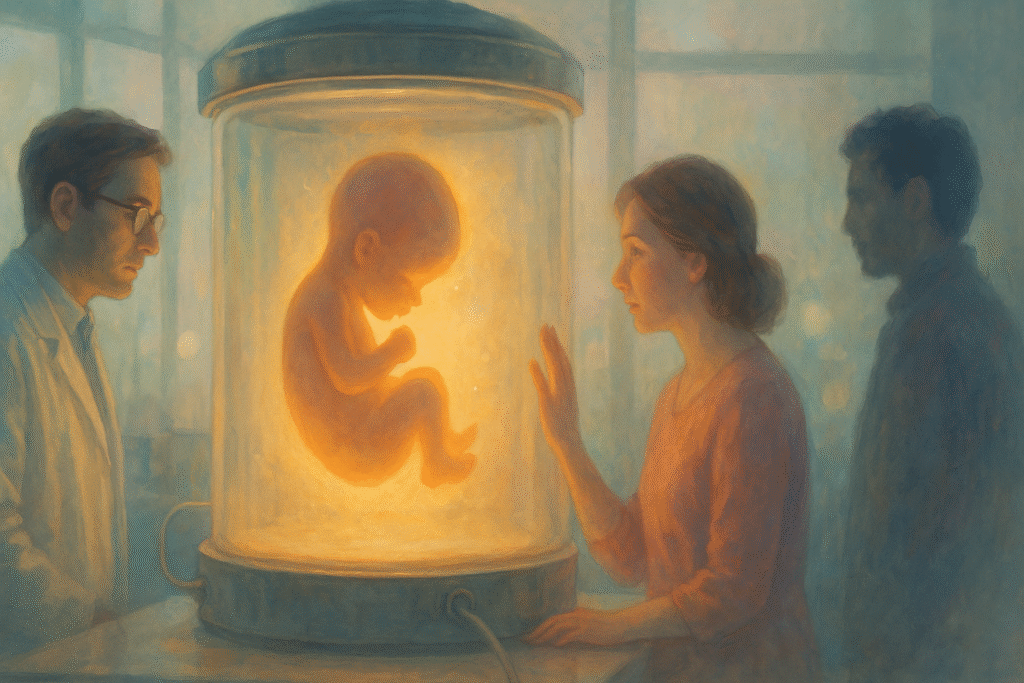

2. Reproductive Rights Revisited

Parental Choice or Social Authority?

Reproductive rights have long been tied to bodily autonomy, especially that of women.

Debates over abortion, IVF, and surrogacy have centered on one question:

Who has the right to decide whether life begins?

Artificial wombs radically alter this framework.

Gestation no longer requires a pregnant body.

As a result, reproduction may be separated from physical vulnerability altogether.

This could expand reproductive possibilities—for infertile individuals, same-sex couples, or single parents.

But it also raises a troubling possibility: does the right to have a child become a right to produce a child?

When reproduction is technologically mediated, life risks becoming a project of desire, efficiency, or entitlement rather than responsibility.

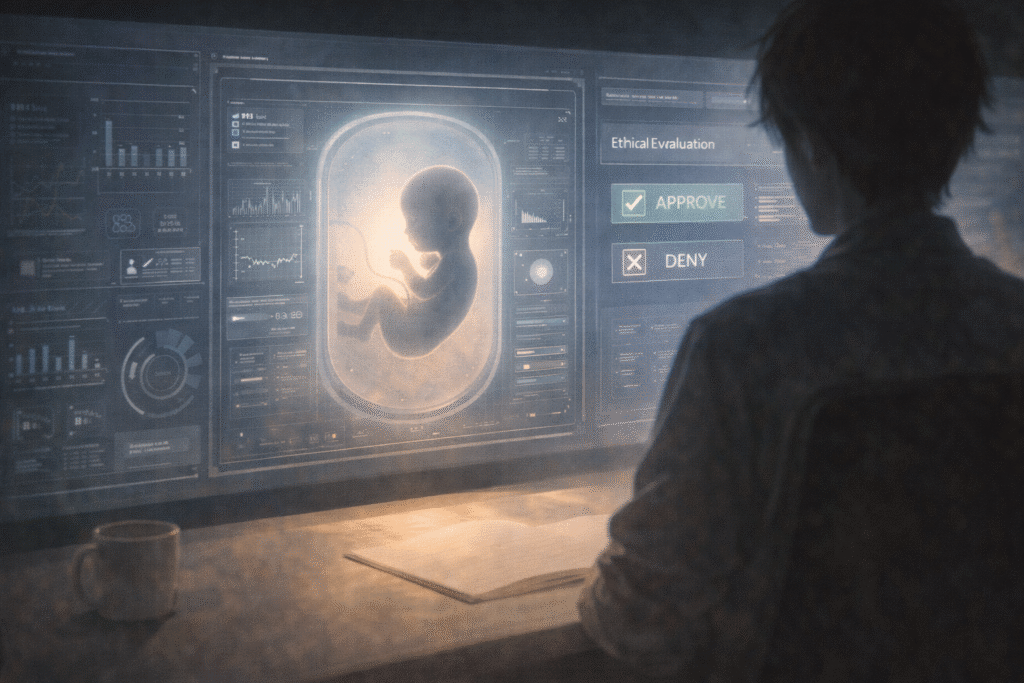

3. State and Corporate Power

Is Life a Public Good or a Managed Resource?

If artificial wombs become viable at scale, who controls them?

Governments may intervene in the name of safety and regulation.

Corporations may dominate through patents, infrastructure, and pricing.

In either case, control over birth may concentrate in the hands of those who control the technology.

Imagine a future in which:

- Access to artificial wombs depends on cost or eligibility,

- Certain embryos are prioritized over others,

- Reproduction becomes subject to institutional approval.

In such a world, birth risks shifting from a human right to a managed resource.

When life becomes trackable, optimizable, and governable, it may lose its moral inviolability and become another system output.

4. A New Ethical Question

Is Life “Given,” or Is It “Made”?

Artificial wombs force us to confront a fundamental moral dilemma:

Is it ethically permissible for humans to manufacture the conditions of life?

Natural birth involves contingency, vulnerability, and unpredictability.

Ectogenesis replaces chance with planning, and emergence with design.

Life becomes not something received, but something produced.

This challenges traditional ethical concepts such as the sanctity of life.

Some argue that technological power demands a new ethics of responsibility:

If humans can create life, they must also bear full moral responsibility for its consequences.

Technology expands possibility—but ethics must decide restraint.

5. Conclusion

Who Chooses That a Life Should Begin?

Artificial wombs represent humanity’s first attempt to fully externalize gestation.

They promise reduced physical risk, expanded reproductive options, and medical progress.

Yet they also carry the danger of turning life into an object of control, ownership, and optimization.

Ultimately, the debate is not only about technology.

It is about meaning.

Is human life something we design, or something we are obligated to protect precisely because it is not designed?

As technology accelerates, society must ensure that ethical reflection moves faster—not slower—than innovation.

References

- Gelfand, S., & Shook, J. (2006). Ectogenesis: Artificial Womb Technology and the Future of Human Reproduction. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

→ A foundational philosophical analysis of artificial womb technology, examining how ectogenesis reshapes concepts of birth, agency, and responsibility. - Scott, R. (2002). Rights, Duties and the Body: Law and Ethics of the Maternal-Fetal Conflict. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

→ Explores legal and ethical tensions between bodily autonomy and fetal interests, offering critical insights into reproductive technologies. - Kendal, E. S. (2022). “Form, Function, Perception, and Reception: Visual Bioethics and the Artificial Womb.” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 95(3), 371–377.

→ Analyzes how the visual representation of artificial wombs shapes public ethical perception of life and technology. - De Bie, F., Kingma, E., et al. (2023). “Ethical Considerations Regarding Artificial Womb Technology for the Fetonate.” The American Journal of Bioethics, 23(5), 67–78.

→ A contemporary ethical assessment focusing on responsibility, care, and social implications of ectogenesis. - Romanis, E. C. (2018). “Artificial Womb Technology and the Frontiers of Human Reproduction.” Medical Law Review, 26(4), 549–572.

→ Discusses legal and moral boundaries of artificial gestation, especially the shifting definition of pregnancy and parenthood.