Rethinking Anthropocentrism in a Changing World

1. Can Humans Alone Be the Measure of All Things?

For centuries, human dignity, reason, and rights have stood at the center of philosophy, science, politics, and art.

The modern world, in many ways, was built on the assumption that humans occupy a unique and privileged position in the moral universe.

Yet today, that assumption feels increasingly fragile.

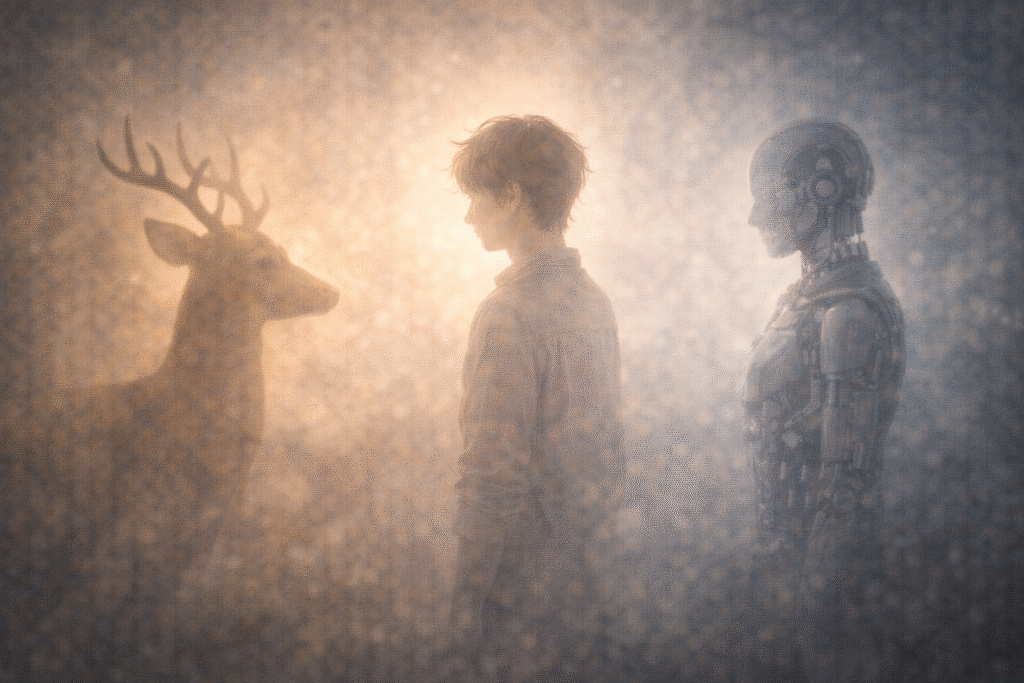

Artificial intelligence imitates emotional expression.

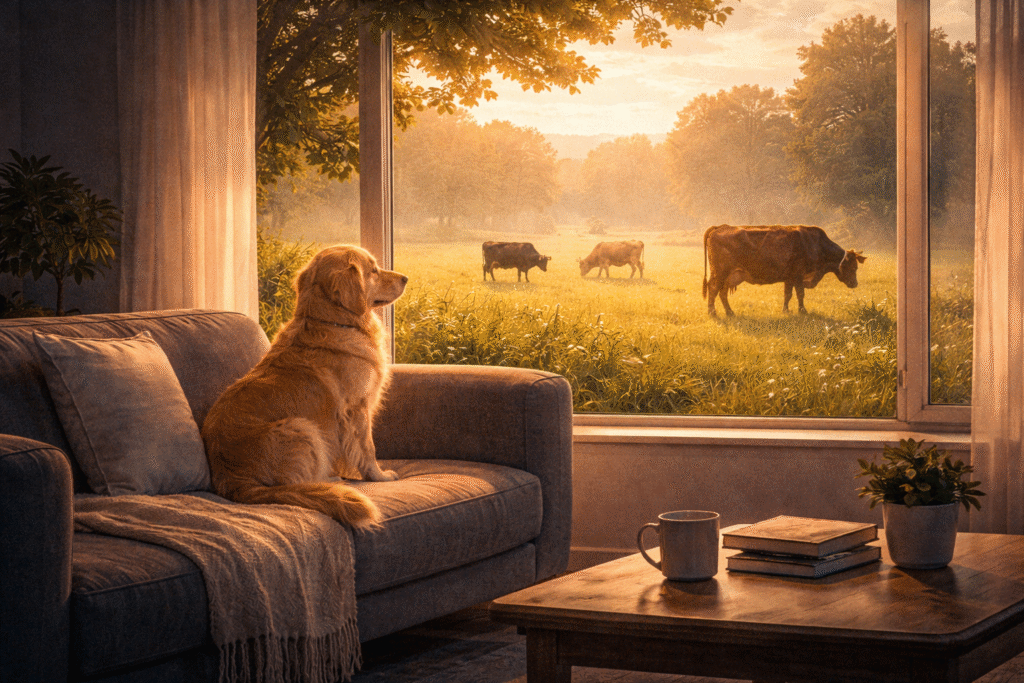

Animals demonstrate pain, memory, and cooperation.

Ecosystems collapse under human-centered development.

Even the possibility of extraterrestrial life forces us to question long-held hierarchies.

At the heart of these shifts lies a single question:

Is anthropocentrism—a human-centered worldview—still ethically defensible?

2. The Critical View: Anthropocentrism as an Exclusive and Risky Framework

2.1 Ecological Consequences

The planet is not a human possession.

Yet history shows that humans have treated land, oceans, and non-human life primarily as resources for extraction.

Mass extinctions, deforestation, polluted seas, and climate crisis are not accidental outcomes.

They are the logical consequences of placing human interests above all else.

From this perspective, anthropocentrism appears less like moral leadership and more like systemic neglect of interdependence.

2.2 Reason as a Dangerous Monopoly

Human exceptionalism has often rested on language and rationality.

But today, AI systems calculate, predict, and even create.

Non-human animals—such as dolphins, crows, and primates—use tools, learn socially, and exhibit emotional bonds.

If rationality alone defines moral worth, the boundary of “the human” becomes unstable.

Anthropocentrism risks turning non-human beings into mere instruments rather than moral participants.

2.3 The Fragility of “Human Dignity”

Even within humanity, dignity has never been evenly distributed.

The poor, the sick, the elderly, children, and people with disabilities have repeatedly been treated as morally secondary.

This internal hierarchy raises an uncomfortable question:

If anthropocentrism struggles to secure equal dignity among humans, can it credibly claim moral authority over all other beings?

3. The Defense: Anthropocentrism as the Foundation of Moral Responsibility

3.1 Humans as Moral Agents

Only humans, so far, have developed moral languages, legal systems, and ethical institutions.

We are the ones who debate responsibility, regulate technology, and attempt to reduce suffering.

Without a human-centered framework, it becomes unclear who is accountable for ethical decision-making.

Anthropocentrism, in this view, is not about superiority—but about responsibility.

3.2 Responsibility, Not Domination

A human-centered ethic does not necessarily imply exclusion.

On the contrary, environmental protection, animal welfare, and AI regulation have all emerged within anthropocentric moral reasoning.

Humans protect others not because we are above them, but because we recognize our capacity to cause harm—and our obligation to prevent it.

3.3 An Expanding Moral Horizon

History shows that the category of “the human” has never been fixed.

Once limited to a narrow group, it gradually expanded to include women, children, people with disabilities, and non-Western populations.

Today, that expansion continues—toward animals, ecosystems, and potentially artificial intelligences.

Anthropocentrism, then, may not be a closed doctrine, but an evolving moral platform.

4. Voices from the Ethical Frontier

An Ecological Philosopher

“We have long classified the world using human language and values.

Yet countless silent others remain. Ethics begins when we learn how to listen.”

An AI Ethics Researcher

“The key issue is not whether non-humans ‘feel’ like us,

but whether we are prepared to take responsibility for the systems we create.”

Conclusion: From Human-Centeredness to Responsibility-Centered Ethics

Anthropocentrism has shaped human civilization for millennia.

It enabled rights, laws, and moral reflection.

But it has also justified exclusion, exploitation, and ecological collapse.

The challenge today is not to abandon anthropocentrism entirely,

but to redefine it—from a doctrine of human superiority into a language of responsibility.

When we question whether humans should remain the moral standard,

we are already stepping beyond ourselves.

And perhaps, in that very act of self-questioning,

we come closest to what it truly means to be human.

References

1. Singer, P. (2009). The Expanding Circle: Ethics, Evolution, and Moral Progress. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

This book traces how moral concern has gradually expanded beyond kin and tribe to include all humanity and, potentially, non-human beings. It provides a key framework for understanding ethical progress beyond strict anthropocentrism.

2. Singer, P. (1975). Animal Liberation. New York: HarperCollins.

A foundational work in animal ethics, this book challenges human-centered morality by arguing that the capacity to suffer—not species membership—should guide ethical consideration. It remains central to debates on anthropocentrism and moral inclusion.

3. Haraway, D. (2003). The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Haraway rethinks human identity through interspecies relationships, arguing that ethics emerges from co-existence rather than human superiority. The work offers a relational alternative to traditional human-centered worldviews.

4. Malabou, C. (2016). Before Tomorrow: Epigenesis and Rationality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

This philosophical work critiques the dominance of rationality as the defining human trait and explores how biological and cognitive plasticity reshape ethical responsibility. It supports a reconsideration of human exceptionalism in contemporary thought.

5. Braidotti, R. (2013). The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Braidotti presents a systematic critique of anthropocentrism and proposes posthuman ethics grounded in responsibility, interdependence, and ecological awareness. The book is essential for understanding ethical frameworks beyond human-centered paradigms.