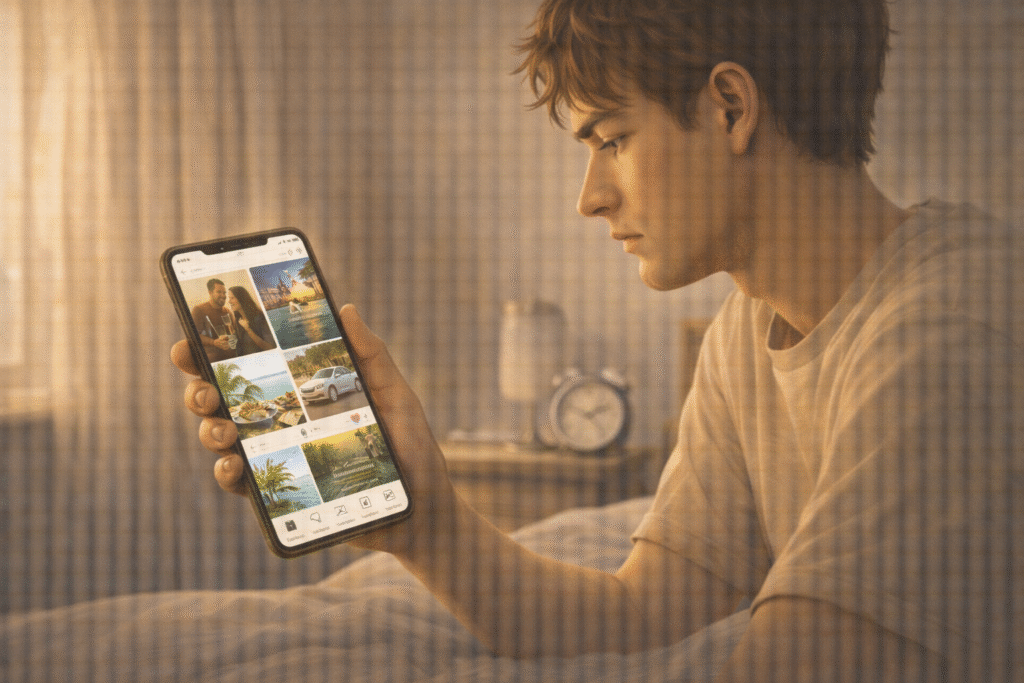

Scrolling through social media has become a daily ritual for many people.

We wake up, reach for our phones, and are immediately greeted by images of vacations, promotions, fitness routines, and seemingly perfect lives.

Yet instead of feeling inspired, many of us experience an unexpected emotional dip.

The reason is simple: social media largely presents highlights, not everyday reality.

As a result, we begin to compare our ordinary lives with carefully curated moments—and a subtle sense of lack begins to grow.

1. The Psychology of Comparison: “Am I Falling Behind?”

People tend to share their happiest and most successful moments online—weddings, travels, career milestones, or idealized lifestyles. These posts create the illusion that others are constantly thriving.

Psychologists describe this tendency as social comparison theory. We unconsciously evaluate our own worth by measuring ourselves against others. On social media, however, this comparison becomes distorted.

A single vacation photo, taken once a year, may appear repeatedly on our feed. Over time, it can feel as though others are always living better lives, reinforcing the belief that we are somehow falling behind.

2. The Highlight Effect and Selective Exposure

Social media content is not neutral—it is selected, edited, and optimized for attention.

A quiet morning coffee rarely competes with a sunset photo taken on a tropical beach.

Platforms dominated by visual content, such as Instagram or TikTok, intensify this effect. Users become increasingly aware of aesthetics, filters, and perfection. In comparison, our own daily routines may start to feel dull or insufficient, deepening psychological dissatisfaction.

3. Algorithms as Emotional Amplifiers

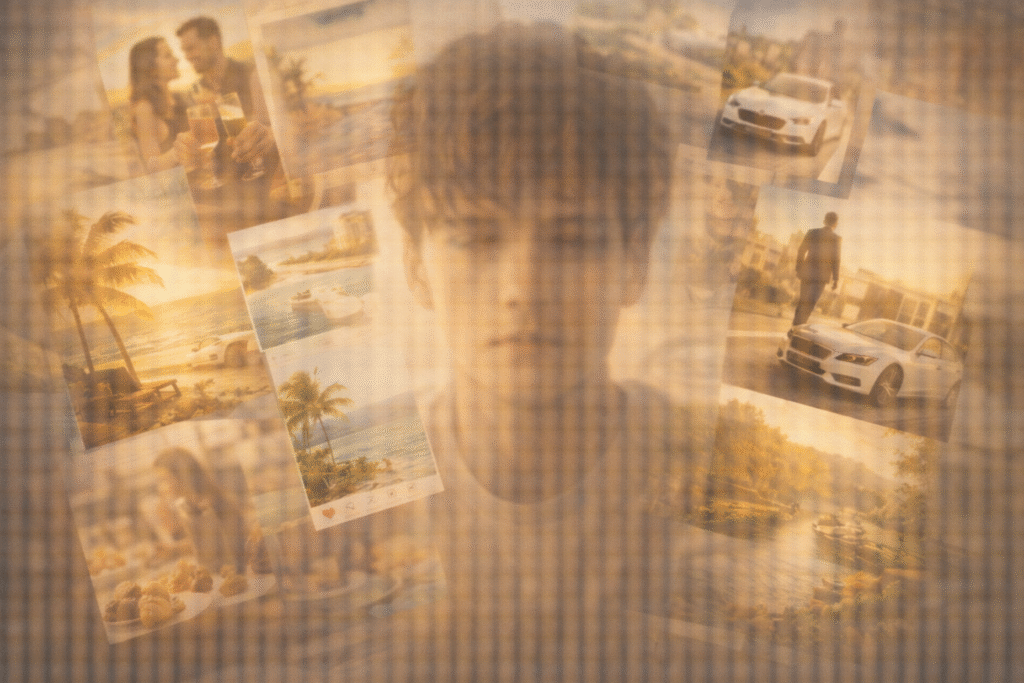

Social media platforms are designed to keep users engaged. Algorithms learn what captures our attention and deliver more of it.

If you interact with luxury travel, fitness influencers, or high-end dining content, similar posts will appear more frequently. Gradually, your feed becomes filled with images of “better” lives—carefully selected to provoke interest, admiration, and often envy.

In this way, social media does not merely reflect reality; it magnifies what we are most likely to compare ourselves against.

4. FOMO and Emotional Fatigue

This persistent comparison often leads to FOMO (Fear of Missing Out)—the anxiety that others are experiencing meaningful moments without us.

A peaceful weekend at home can suddenly feel empty when confronted with group photos from a trip or event. When such experiences accumulate, they can result in emotional exhaustion, reduced self-esteem, and even depressive feelings.

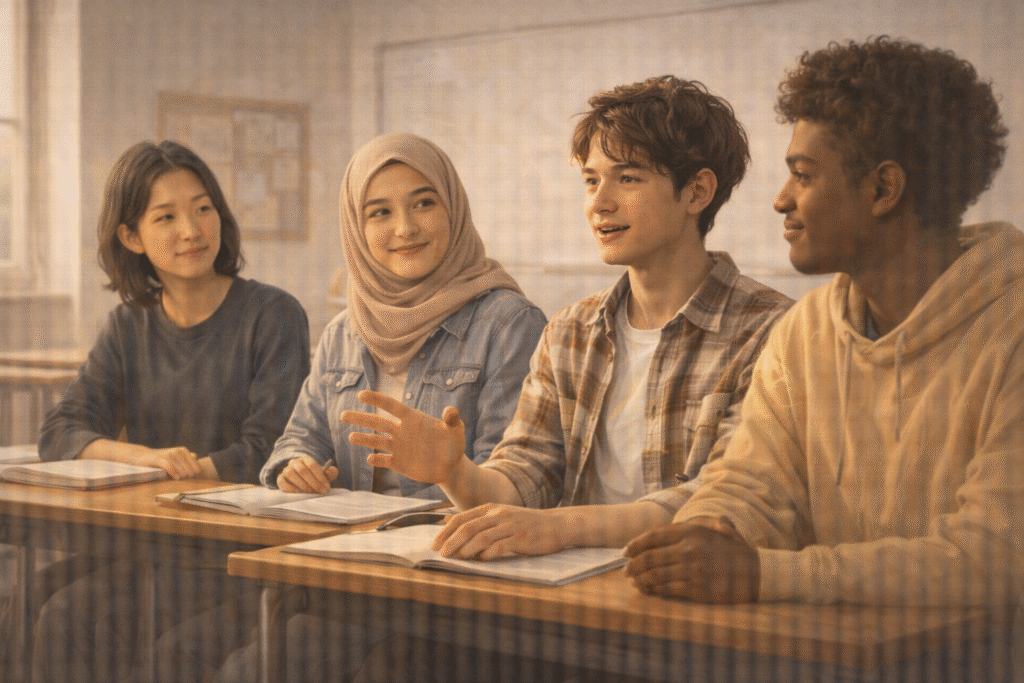

Research suggests that adolescents and young adults are particularly vulnerable, as repeated exposure can foster the belief that their lives are less exciting or less valuable.

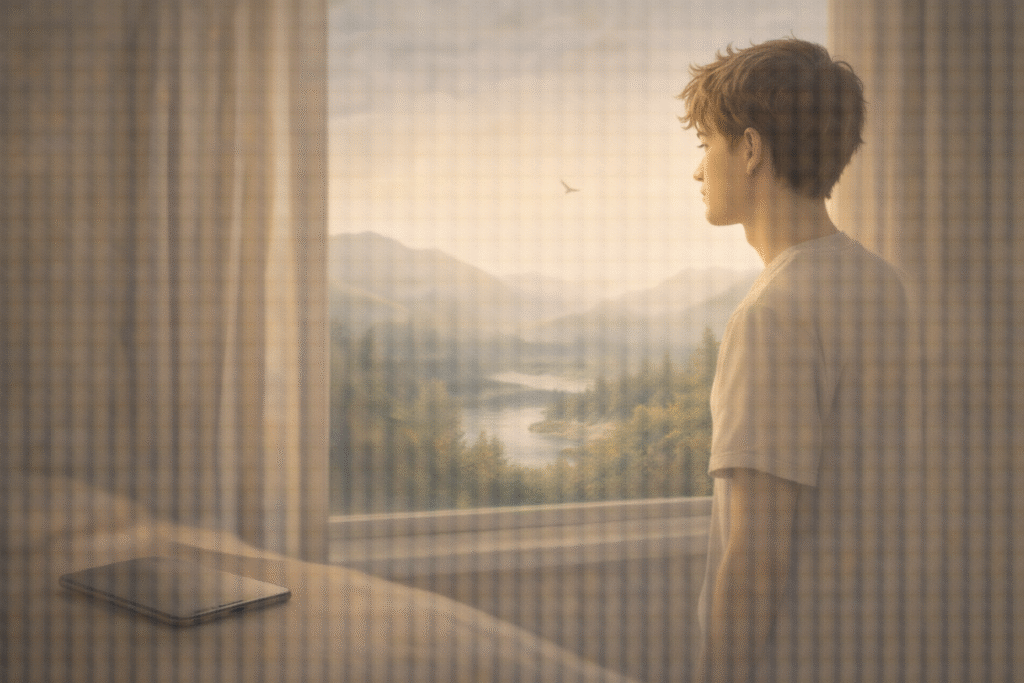

5. Using Social Media Without the Sense of Lack

Social media itself is not inherently harmful. The key lies in how we use and interpret it.

- Intentional use: Log in with a purpose—learning, inspiration, or connection—rather than endless scrolling.

- Reality awareness: Remember that posts represent fragments, not complete lives.

- Time boundaries: Setting daily limits can significantly reduce emotional fatigue.

When approached mindfully, social media can shift from a source of deficiency to a tool for motivation and insight.

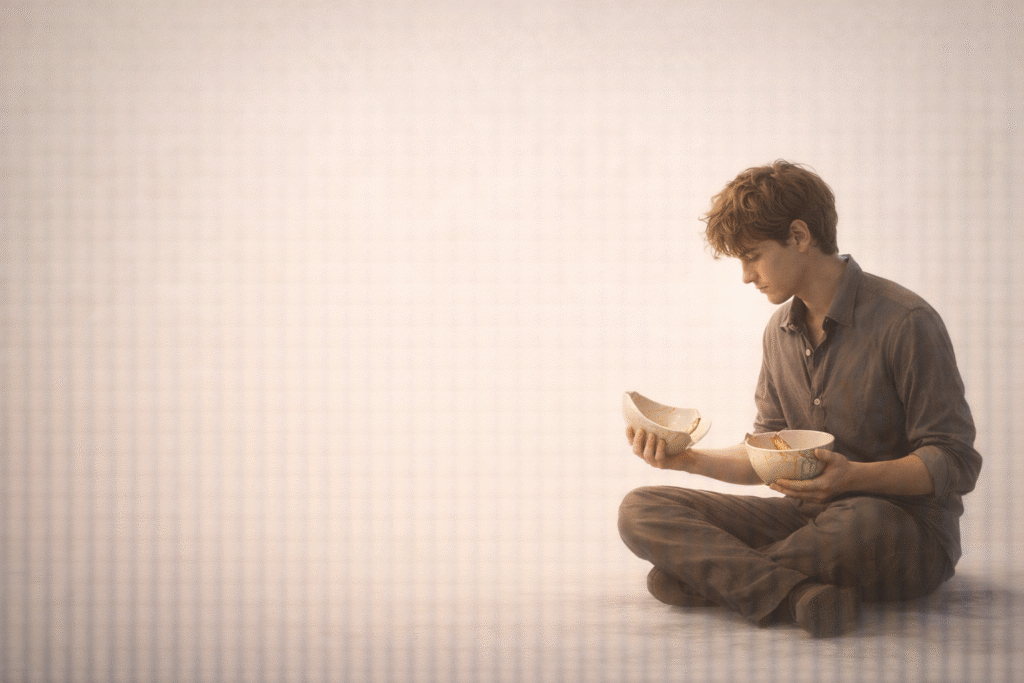

Conclusion

Social media functions like a distorted mirror—one that reflects only the brightest moments of others while obscuring the full picture. When we mistake highlights for reality, we risk undervaluing our own lives.

The challenge is not to reject social media entirely, but to reclaim perspective.

By recognizing the difference between curated images and lived experience, we can transform social media from a space of comparison into one of connection and self-awareness.

References

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(4), 206–222.

→ This study empirically examines how social comparison on social media affects self-esteem, highlighting the role of upward comparison in feelings of inadequacy.

Chou, H. T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(2), 117–121.

→ Demonstrates how social media users systematically overestimate others’ happiness, reinforcing perceived personal deficiency.

Tandoc Jr., E. C., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 139–146.

→ Explores the link between social media use, envy, and depressive symptoms, offering insight into long-term emotional consequences.