“What is your name?”

This simple question sounds innocent enough.

We ask it to remember someone, to recognize them, to understand who they are.Yet behind this everyday act lies something deeper.

When we give something a name, are we merely identifying it—

or are we defining, framing, and quietly exercising power over it?

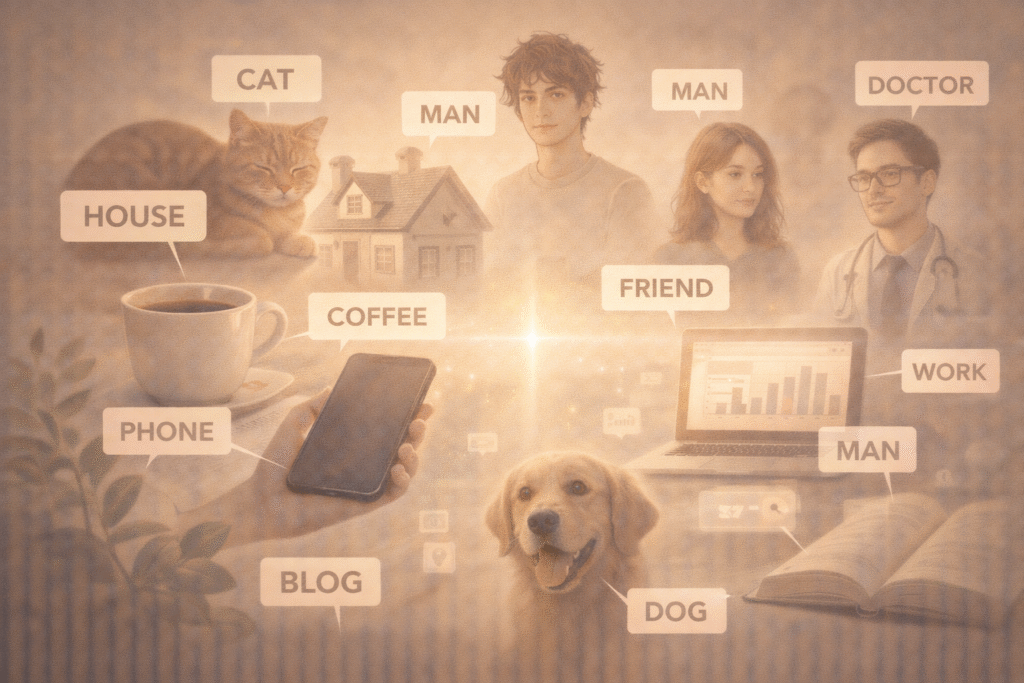

We live surrounded by names.

Names for people, places, objects, social groups, and abstract ideas.

But naming is never neutral.

To name something is often to decide how it will be seen, treated, and remembered.

1. Naming Is Never Just a Label

We often say that we “give” names, as if naming were a harmless convenience.

Yet the moment something is named, it becomes separated from everything else and fixed within a category.

A name does not simply point—it interprets.

Consider a few familiar examples:

- Calling a plant a “weed” turns a living organism into something unwanted.

- Labeling a country as “underdeveloped” freezes complex histories into economic deficiency.

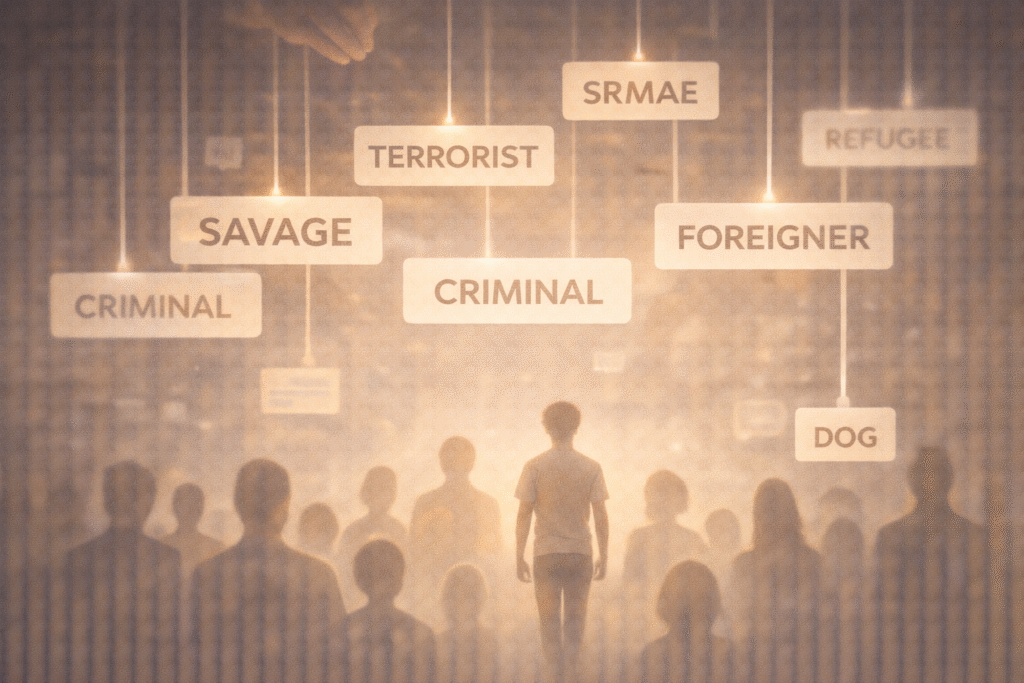

- Words like “criminal,” “disabled,” or “elderly” often overshadow individual stories with simplified identities.

In this sense, naming does not just describe reality—it actively shapes how reality is understood.

2. Who Gets to Name? Power Speaks First

Names rarely emerge from equal positions.

More often, they flow from the powerful to the powerless.

Throughout history, naming has been deeply political:

- Colonial powers renamed lands they occupied, overwriting indigenous names and identities.

- Administrative systems imposed categories that reorganized populations for governance and control.

- Minority groups were recorded, classified, and often reduced to labels they did not choose.

To name is to organize the world—and those who control naming often control meaning itself.

3. Naming as a Tool of Framing and Persuasion

In contemporary society, naming has become a battleground of perception.

- Branding turns ordinary products into lifestyles through carefully chosen names.

- Political framing contrasts terms like “tax relief” versus “tax burden” to steer public emotion.

- Social media labels and nicknames can elevate, ridicule, or permanently reduce a person to a single trait.

A name can condense complex realities into a single emotional shortcut.

It tells us not only what something is, but how we should feel about it.

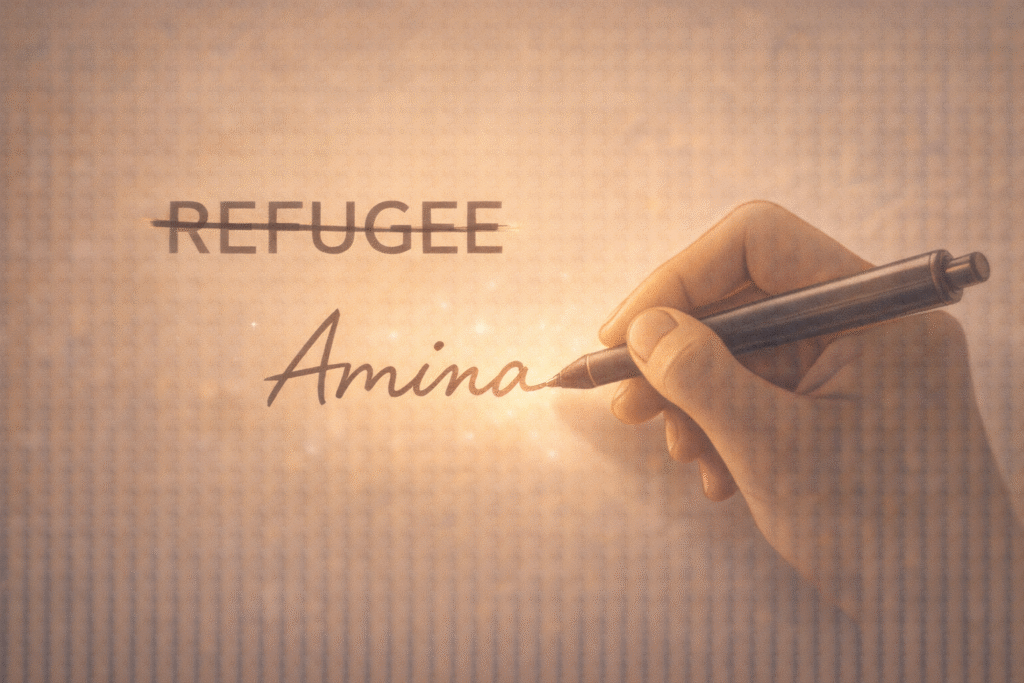

4. Renaming as Resistance and Responsibility

Yet naming is not only a mechanism of domination.

It can also be a site of resistance, care, and ethical reflection.

When people reclaim names—or choose new ones—they reshape relationships:

- Individuals asserting self-chosen names affirm autonomy and dignity.

- Public language shifts toward more respectful terms reshape social attitudes.

- Renaming becomes an act of seeing others differently, not as objects but as subjects.

To rename is not to change the world itself, but to change how we stand in relation to it.

Conclusion: What Do Our Words Reveal?

An ancient phrase says, “In the beginning was the Word.”

It reminds us that language does not merely reflect reality—it helps create it.

Every name carries a perspective.

Every label contains a judgment, whether intended or not.

So perhaps the real question is not whether naming involves power—

but what kind of power we choose to exercise through our words.

How we name others may quietly reveal how we see them,

and ultimately, how we choose to live alongside them.

References

1.Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Pantheon Books.

→ Explores how language, classification, and discourse function as systems of power that shape what can be known and said.

2.Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. University of Chicago Press.

→ Demonstrates how naming and categorization reflect cognitive structures that influence perception and culture.

3.Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. University of Illinois Press.

→ Examines how marginalized groups are named and silenced within dominant discourses, revealing naming as a political act.

Leave a Reply